As this strange year of 2021 has come to an end, we can reflect on 2021 being a massive year for the topic of the domestication of the horse. I find this one of the most fascinating events in human history, and the data which has come out this year has shone a new light on this topic, and revealed some long-sought answers.

As is typical, in what was supposed to be a summary of some recent articles I fell into a few rabbit holes and ultimately spent a month or so working on this entry, roughly equating to about 60 pages. A lot of it is opinion based, and I'd love to see disagreements being voiced. I also took some breaks, add the holidays to that and what was supposed to be an early December post became a Post-New Year's special.

In this post I will be going over the domestication of the horse, the development and spread of charioteering and the development of horseback riding. But before all that, let's have a look at the relation between man and horse on the steppes before their domestication.

However, the end of the ice-age brought a period of woodland development, which in combination with human hunting led to their numbers significantly decreasing. The onset of the Neolithic however, may have led to the re-spread of the European wild horse, as the neolithic spread also led to significant deforestation. In the Americas, not much after the progenitors of the native Americans crossed over the American wild horse went extinct.

In Eastern Europe, the horse never stopped being a factor, although over time their numbers were dwindling as well. The same goes for Central Asia, Siberia and Anatolia, to name a few regions.

The Botai and Tersek sites of eneolithic Kazakhstan are particularly worth mentioning. These sites, dating from 3700 BC to 3000 BC are noteworthy due to the high amount of horse bones present. Furthermore, analysis of teeth had shown signs erosion consistent with bitwear, which would suggest that the Botai may have ridden their horses.Then Outram et al. found suggestive evidence that the Botai drank mare's milk, as the fat lipids on their pottery were consistent with that of a horse.

"Before 3700 BCE foragers in the northern Kazkah steppes lived in small groups at temporary lakeside camps such as Vinogradovka XIV in Kokchetav district and Tel'manskie in Tselinograd district. Their remains are assigned to the Atbasar Neolithic.31 They hunted horses but also a variety of other game: short-horned bison, saiga antelope, gazelle, and red deer. The details of their foraging economy are unclear, as their camp sites were small and ephemeral and have yielded relatively few animal bones.Around 3700-3500 BCE they shifted to specialized horse hunting, started to use herd-driving hunting methods, and began to aggregate in large settlements—a new hunting strategy and a new settlement pattern. The number of animal bones deposited at each settlement rose to tens or even hundreds of thousands. Their stone tools changed from microlithic tool kits to large bifacial blades. They began to make large polished stone weights with central perforations, probably for manufacturing multi-stranded rawhide ropes (weights are hung from each strand as the strands are twisted together). Rawhide thong manufacture was one of the principal activities Olsen identified at Botai based on bone tool microwear.For the first time the foragers of the northern Kazakh steppes demonstrated the ability to drive and trap whole herds of horses and transport their carcasses into new, large communal settlements. No explanation other than the adoption of horseback riding has been offered for these changes."

"Given this early economic interest in horses, which now appears to have involved a developed form of pastoralism, it is not surprising to find evidence for the ritual use of horses at Botai culture sites. Botai houses are semi-subterranean structures frequently surrounded by sizeable pits. These pits rarely appear to contain random domestic refuse; instead they are filled with placed deposits of carefully selected materials. In particular, there is a significantly high number of pits that contain horse skulls, sometimes with accompanying articulated cervical vertebrae and there is some evidence that horse frontal bones have been modified to form masks. Pits to the west side of houses commonly contain either whole dogs or dog skulls in association with horse skulls, necks, pelves or foot bones. With regard to foot bones, horse phalanges are frequently decorated with incised marks and a cache of phalanges has been found within a house at the Botai culture site of Krasnyi Yar."

"Comparing our results to the Botai tooth provides strong indication that the osteological features taken for evidence of horse transport, may have been produced solely through natural processes. Although our analysis suggests that it is uncommon for enamel hypoplasia pits to co-occur in multiples on the anterior margin of the tooth, one wild horse in our sample, from Bluefish Cave I (MgVo-1) in northern Yukon, exhibited two such pits, nearly identical to those attributed to bit wear at Botai, along with visible cementum banding (Fig. 3). Based on available data, we are unable to speculate on whether enamel hypoplasia itself might occur in higher frequency or severity in domestic and wild samples. However, the high frequency of enamel hypoplastic defects with dentine exposed in North American horses suggests that dentine exposure—in the form of circular or oval pits—cannot be considered reliable evidence of transport damage. In fact, the apparent frequency of this type of damage in the Botai assemblage (1/9 or 11.1%10) is commensurate or even below the frequency of this type of feature observed in wild North American populations (15.3%; Table 1)."

"In light of our new data, arguments for horse domestication at Botai no longer appear to be supported by the available archaeological evidence. Without the presumption of horse transport, many aspects of the Botai assemblage are more efficiently explained by interpretation of the site as the result of regularized mass-harvesting of wild horses. For example, Botai’s location at a river crossing is consistent with wild equid hunting tactics that date back deep into the Pleistocene. At Paleolithic sites across Europe, entire bands of horses—either mostly-female harem groups, all-male bachelor bands, or both—were commonly ambushed alongside natural water features where they were more effectively trapped and slaughtered46. This strategy appears to have been employed by the earliest hominin horse hunters, dating back nearly a half million years or more47,48. Group harvesting at Botai could easily explain unresolved questions in the assemblage, including apparent presence of entire carcasses, the predominance of prime-aged adult animals, and the recovery of bone arrowheads in situ with deceased horse remains, as well as the utter absence of other domestic fauna at Botai22. The relatively equal ratios of male and female animals found at Botai could imply that the site was used to harvest both bachelor bands and harem groups over its use history. Summer seasonality identified by Outram et al.10 using isotope data could reflect horse milk production, but many mass harvesting sites of horses also display consistent summer seasonality, even over centuries or millennia of reuse49. If chosen for a favorable topographic position or location on a key ecological corridor or migration route, horse mass harvesting sites may have been regularly utilized in a particular time of year over long stretches of time.A reappraisal of the pre-Botai archaeological record of humans and horses also supports this view. Many of the cultural modifications found in the Botai artifact assemblage—the decoration of horse bones, the use of horse bones as tools, and even the occasional ritual inhumation of horse remains—are fully consistent with hunter-gatherer cultures in which horse hunting plays an important role. Horses are the most commonly depicted animal in Eurasian Paleolithic cave paintings50, and were a favorite muse for hunter-gatherer artists across the Pleistocene and into the Holocene—appearing on bones, ivory, or stone objects—and probably many organic artifacts that have not survived—as decorations or as dedicated votives51. The discoveries of ritual features and artwork at Botai or Eneolithic sites from the Black Sea region, while important, fail to effectively delineate a domestication relationship from the rich hunting tradition that preceded it."

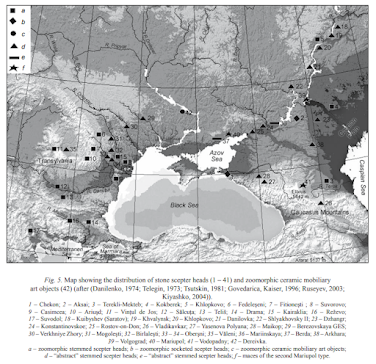

Turning to the Eastern European steppe regions, we see that the hunter-gatherers were mostly situated along the river beds and relied heavily on fishing to supply their diet. Boars, Saiga deer, and the horse were some of the animals chased by these foragers Among these steppe societies see a tradition emerging of horsehead scepters amongst the neolithic foragers of the Samara culture, a ttraditio which spread through the steppes during the eneolithic with the Khvalynsk culture and the Suvorovo-Novodanilovka groups. We also see the deposition of horse bones into graves, as well as engraved horse teeth and bones.

The increase in the numbers of horse bones found at Dereivka and other Chalcolithic sites, in contrast to earlier Holocene deposits, has been used as evidence that the horses from Dereivka were domesticated (Bokonyi 1984). In fact, except in the case of cemeteries, onlyrelatively small quantities of horse skeletal material are normally recovered from sites dated to periods when domesticated horses were common - for example, during Roman and medieval times. Therefore, although the increase in the quantity of horse bones probablyindicates that there was, during the Chalcolithic, a change in the way that horses were exploited, it is not proof of domestication. Instead, the evidence strongly suggests that horse hunting had become intensified.

Milking horses.

Our study of dental calculus from the Eneolithic site of Botai to the east, where early horse milking has been suggested by lipid analysis (albeit equivocally), did not yield milk proteins. Although two samples are insufficient for drawing broad conclusions, this finding does not support widespread milk consumption at the site. However, two calculus samples from Early Bronze Age individuals of the Pontic–Caspian region do provide evidence for the consumption of horse milk. Combined with archaeogenetic evidence that places the Botai horses on a different evolutionary trajectory than the domesticated DOM2 E. caballus lineage, this finding—if backed up by further sampling and analysis—would seem to firmly shift the focus of sustained early horse domestication on the Eurasian steppe to the Pontic–Caspian region. So far, the oldest horse specimens that carry the DOM2 lineage date to between 2074 to 1625 calibrated years BC, at which time the lineage is archaeologically attested in present-day Russia, Romania and Georgia. Our identification of—to our knowledge—the earliest horse milk proteins yet identified on the steppe or anywhere else reveals the presence of domestic horses in the western steppe by the Early Bronze Age, which suggests that the region (where the first evidence for horse chariots later emerged at about 2000 BC) may have been the initial epicentre for domestication of the DOM2 lineage during the late fourth or third millennium BC.

Archaeological information of the site:

Krivyanskyi IX (Number of Individuals: 2; Individual Archaeology Codes: EBA: KRI9 K.4 N-21; KRI9 K.2 N-2) This burial ground is located between three small rivers in the Don basin, 30 km northeast of Rostovon-Don. It consists of seven kurgans that in total contained 92 burials. The site was used from the Eneolithic through the LBA, and also included some later household pits of the medieval Khazar period. The analyzed archaeological remains come from four mounds; the earliest phase of mound construction dates to the EBA Yamnaya culture (No. 1, 2, 4) and MBA (No. 5).

The EBA burials were in pit graves, the MBA burials were interred in catacombs. Individual and collective burials (up to five skeletons), with traces of ochre, were characteristic of both periods. There were few funeral offerings or artifacts in any of these graves; and most of the deceased had no accompanying artefacts. Exceptions include a single ceramic vessel in one burial from the Yamnaya culture, as well as a stone flake and small cattle bones in one of the MBA Catacomb burials.

Radiocarbon dates from individuals sampled in the present study: KRI9 K.4 N-21A: 3345 to 3096 cal BCE (4495±25 BP, PSUAMS-7979) This was a collective grave containing five individuals, two adults and three immatures. The dental calculus sample was taken from adult A, pictured below. A second date on adult C was significantly different: 2904-2701 calBCE (4225±25 BP, PSUAMS-7980). KRI9 K.2 N-2: 2881 to 2633 cal BCE (4165±25 BP, PSUAMS-7978) This was a single grave containing an EBA ceramic vessel.

At this archaeological site belonging to the Yamnaya culture we have what I consider the current oldest, unequivocal evidence of horse domestication. The article also highlighted that neither of the two Botai samples showcased signs of milk consumption either, which would be at odds with the interpretation of the Botai site being one where mare's milk was readily available. Combining this with the previously mentioned point in regards to bitwear, it doesn't seem like the relation between Botai and their horses went beyond hunter and prey. Another interesting point is the lack of dairy consumption at Khvalynsk.

Unfortunately we cannot tell much about the preceding periods. While we now have confirmation that mare's milk was consumed in the Yamnaya culture, as had been proposed by archaeologists, we don't exactly know when this began, yet. If the teeth match the pots with the Yamnaya, perhaps it would match as well with Repin, Mikhailovka, Middle Stog etc? Khvalynsk was also suggested to have been a society of mare's milk drinkers and they were barely milk drinkers in general let alone mare's milk, as was also revealed in this article. But then again the archaeology already made it clear it was a society which still heavily relied on fishing, and most animals were kept as a form of wealth storage and/or status symbol.

Some care should be taken with this finding in regards to extrapolating it to preceding periods, but I think it is probable that the late 5th or early 4th millenium b.c saw the initial domestication of the horse amongst the people of the eneolithic Sredny Stog culture.

And while we finally know that the Yamnaya did domesticate their horses, we don't really know much else. How do their horses relate to the modern horse breeds? Did they have functions besides providing milk and meat? are all questions not addressed in this article. Luckily it was only one of the several papers containing major findings in regard to this topic. Let's take a look at the most ambitious one of 2021.

The origins and spread of domestic horses from the Western Eurasian steppes

I'm assuming that because of the title, several articles reporting on this study also misunderstood the origin and spread of the DOM2 as the starting point of horse domestication. Take this sentence from an pop science article titled "We've found the time and place that horses were first domesticated": "One of the most stubborn mysteries in prehistory has finally been reined in. A massive study of ancient DNA has revealed where horses were domesticated: around 2200 BC on the steppes of central Eurasia, near the Volga and Don rivers in what is now Russia.".

Then you have this gem;

Our results reject the commonly held association between horseback riding and the massive expansion of Yamnaya steppe pastoralists into Europe around 3000 BC8,9 driving the spread of Indo-European languages. This contrasts with the scenario in Asia where Indo-Iranian languages, chariots and horses spread together, following the early second millennium BC Sintashta culture.

This may read as simply "Yamnaya did not ride horses'', which may or may not be true, but this 'expansion of yamnaya steppe pastoralists into Europe' is in reference to the on-set of the Corded Ware cultural horizon, which has yet to been proven to have actually arose from "a massive expansion of Yamnaya steppe pastoralists". What they are saying is that the Corded Ware did not bring their steppe horses further west and north into Europe if their forebears had steppe horses to begin with.

I feel a lot of the misunderstandings caused by this article, as well as my little rant here, could've been avoided by the authors using clearer language in their article. I also think this study could have been fleshed out better by including more samples from the Corded Ware culture, the Bell Beaker culture (rather than a singleton wild sample from a Portuguese eneolithic fortress classified as Bell Beaker due to a few pottery shards), Fatyanovo culture, Abashevo culture and the Bactria-Margiana archaeological complex to name a few. Hell even some of the potential equid bones found at late Harappan would have been great information, regardless if they were even genuinely horses and whether they had been domesticated or not.

Aside from that, this article has given us some terrific insights. To sum it up:

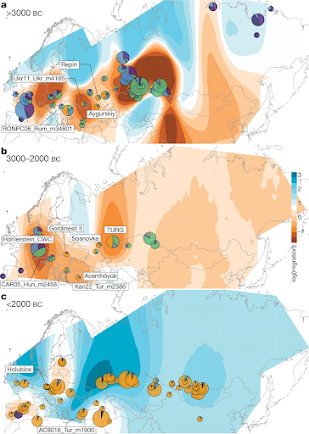

- Western and Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Central Asia and Anatolia all had distinct populations of wild horses.

- The horses of the Pontic-Caspian Steppe around belonged to the NEO-NCAS (Neolithic), C-PONT (EBA), TURG (Late Yamnaya) breeds, horse populations which the DOM2 breed ultimately emerged

- The tested Corded Ware horses were all of native European origin rather than Pontic-Caspian derived horses

- DOM2 horses show up after 2200 BC, after which they rapidly disperse through Eurasia

- DOM2 horses show selection for GSDMC and ZFPM1, which impact back pain and behaviour respectively

- Tarpan horses were wild horses and may have originated in Ukraine

However when taking into account the archaeological record I don't think we would find some major overhauling new data in Corded Ware sites, as horse bones are frequently found in Corded Ware sites. As far as I know there are none in Corded Ware sites in the East Baltic for example.

To quote Marsha Levine again, she makes a great relevant point about horse domestication here:

Furthermore, considering the problems encounteredby modern collectors trying to breed Przewalski’shorses, it seems likely that horse-keeping would havehad to have been relatively advanced before con-trolled breeding over successive generations, and thusdomestication, would have been possible. As Boydand Houpt point out: ‘Failure to consider the typicalsocial organization of the species can result in prob-lems such as pacing, excessive rates of aggression,impotence and infanticide’ (Boyd & Houpt, 1994,p. 222). Thus, in order to breed wild horses success-fully in captivity, their environmental, nutritional andsocial requirements must be met.

The cognitive and logistical difficulties involved increating such an environment at the time of the earliest horse domestication should not be underestimated. Although it is not possible to know for sure that theancestor of the domestic horse would have been moreamenable to captive breeding than the Przewalski’s. That capturing wild horses and stealing tamed or domesticated ones was regarded by the Plains tribes as preferable to breeding them supports the scenario proposed here. If it is correct, it seems likely that there would have been a relatively long period of time when new horses would have been recruited from wild populations. This could have been carried out by trapping, driving and chasing, as documented for the Mongols and North American Plain stribes (Levine, 1999a).

This depiction of a Corded Ware mounted warrior may not be all too accurate it seems, but there still is some hope.

The first cluster are the NEO-NCAS horses, which was the profile typical of the wild horses of the Neolithic western steppes. Horses from Samara, the North Caspian delta and the Volga-Don region belonged to this genetic cluster. These are the horses you saw reflected on the stonehead scepters earlier.

During the eneolithic and bronze age the horses are grouped as C-PONT, which show an increased relation to DOM2 in comparison with the eneolithic NEO-NCAS horses seen in the steppes of Eastern Europe.

Yamnaya horses at Repin and Turganik carried more DOM2 genetic affinity than presumably wild horses from hunter-gatherer sites of the sixth millennium BC (NEO-NCAS, from approximately 5500–5200 BC), which may suggest early horse management and herding practices. Regardless, Yamnaya pastoralism did not spread horses far outside their native range, similar to the Botai horse domestication, which remained a localized practice within a sedentary settlement system.

A potential clue in favour of the suggestion that early horse management was a factor is that one of the C-PONT samples came from the steppe Maykop culture of the southern Russian Steppes. While these people had a very similar lifestyle to that of the Yamnaya, they had different origins and were related to the kurgan giants I featured in an earlier post. Considering technologies such as wagons were shared by these peoples, tamed horses could perhaps also have been shared Alternatively the increased affinity with DOM2 came from a genetic bottleneck which occurred as wild horses were hunted during the neolithic, with the C-PONT horses at diverse sites being local wild horses.

Following the Sosnovka samples, there is a seven century gap in steppe horse samples until we get to the Sintashta culture and it's relatives, who only had DOM2 horses. From there on out do we see a massive distribution of DOM2 horses. One interesting aspect of the DOM2 horse which has been a major driver for their expansion is that they all carried adaptations at GSDMC and ZFPMI, which the previous breeds did not.

Human-induced DOM2 dispersal conceivably involved selection of phenotypic characteristics linked to horseback riding and chariotry. We therefore screened our data for genetic variants that are over-represented in DOM2 horses from the late third millennium BC (Extended Data Fig. 7). The first outstanding locus peaked immediately upstream of the GSDMC gene, where sequence coverage dropped at two L1 transposable elements in all lineages except DOM2. The presence of additional exons in other mammals suggests that independent L1 insertions remodelled the DOM2 gene structure. In humans, GSDMC is a strong marker for chronic back pain29 and lumbar spinal stenosis, a syndrome causing vertebral disk hardening and painful walking.The second most differentiated locus extended over approximately 16 Mb on chromosome 3, with the ZFPM1 gene being closest to the selection peak. ZFPM1 is essential for the development of dorsal raphe serotonergic neurons involved in mood regulation31 and aggressive behaviour32. ZFPM1 inactivation in mice causes anxiety disorders and contextual fear memory. Combined, early selection at GSDMC and ZFPM1 suggests shifting use toward horses that were more docile, more resilient to stress and involved in new locomotor exercise, including endurance running, weight bearing and/or warfare.

The authors didn't provide solid information on when these markers were selected for, although it had to be completed by 2200 BC-ish. I have no clue how long this process would take. Although horses reach sexual maturity in little over a year and can bread for quite a long period, I'd imagine it would have taken some time and generations. Let's say it's two centuries from a regular population of half wild half domestic milk and winter meat providing horse stocks to bottlenecked horses primed for riding and charioteering. In such a scenario the process must've begun with a population which inhabited the Don-Volga steppes in the mid-third millennium BC. But maybe it was a much faster process? Or a slower one?

The exact origin of the DOM2 horse has not been revealed yet. The article gives a rough time frame and region, but does not put down their finger in attributing this horse breed to a particular culture. It does however seem to point slightly towards the Yamnaya and Poltavka/Catacomb circle of the Early bronze age steppes, with their suggestion that the DOM2 horse arose on the Volga-Don Steppes and may have been partially derived from the type of horses seen at Turganik. Note though that the Turganik samples were less similar to the DOM2 in genetic make-up than the C-PONT horses.

The C-PONT group not only possessed moderate NEO-ANA ancestry, but also was the first region where the typical DOM2 ancestry component (coloured orange in Fig. 1e, f) became dominant during the sixth millennium BC. Multi-dimensional scaling further identified three horses from the western lower Volga-Don region as genetically closest to DOM2, associated with Steppe Maykop (Aygurskii), Yamnaya (Repin) and Poltavka (Sosnovka) contexts, dated to about 3500 to 2600 BC (Figs. 2a, b, 3a). Additionally, genetic continuity with DOM2 was rejected for all horses predating about 2200 BC, especially those from the NEO-ANA group (Supplementary Table 2), except for two late Yamnaya specimens from approximately 2900 to 2600 BC (Turganik (TURG)), located further east than the western lower Volga-Don region (Figs. 2a, b, 3a). These may therefore have provided some of the direct ancestors of DOM2 horses.

Kırklareli-Kanlıgeçit is an Early Bronze Age settlement mound located in Thrace Turkey, dating back to ~2600-2400 cal. BCE. Excavations have revealed a large faunal assemblage, consisting mainly of remains of domestic animals, including cattle, sheep/goat, pig and horse, including the horse specimen labelled Kan22_Tur_m2386, while wild animals only represent 8% of the animal fossil record. Morphometric analyses on animal bones indicate that horses at Kırklareli-Kanlıgeçit were strong and resilient animals, likely used for riding and/or as labour work force.

"The complete absence of horse bones in Neolithic and Chalcolithic faunal assemblages from Thrace either indicates that wild horses did not occur at all in this region during the mid-Holocene or that their numbers were so small that only in very rare cases did they become hunters’ prey. The first possiblity appears to be more likely. The Balkan mountains probably marked a natural boundary of distribution for Equus ferus in the Postglacial. North of the mountains, in the lower Danube area, wild horse is repeatedly documented by single bone finds in deposits of various Neolithic sites (e.g. Necrasov et al. 1967: Fig. 2).

From the above observations one can conclude that the Early Bronze Age horse remains from Kırklareli-Kanlıgeçit probably belonged exclusively to domestic horses. The material of this site can be regarded as the oldest stratigraphically and chronologically unambiguous evidence for the presence and keeping of domestic horses in the southern Balkan Peninsula."

On the beginning of horse husbandry in the southern Balkan peninsula - The horses from Kirklareli̇-Kanligeçi̇t (Turkish Thrace)- N. Benecke

Their osteological conclusions were that the horses of the eastern european steppes were an unlikely direct predecessor, instead opting for an Anatolian origin. They did justly say that they did not have any data from the lower Danube to compare, with the assumption that these horses would've been an extension of the steppe horse population. But we do have data from the lower Danube region now, in the form of ancient equid genetics and the ENEO-ROM horses from this region were the main ancestor of Kan22_Tur_m2386.

In addition, a contribution from such horses had also been noted in a horse sample from 3rd millennium BC Hungary, which in turn was modeled as having a 50-67% genetic contribution from horses such as Kan22_Tur_m2386.

DOM2 ancestry reached a maximum 12.5% in one Hungarian horse dated to the mid-third millennium BC and associated with the Somogyvár-Vinkovci Culture (CAR05_Hun_m2458). qpAdm17 modelling indicated that its DOM2 ancestry was acquired following gene flow from southern Thrace (Kan22_Tur_m2386), but not from the Dnieper steppes (Ukr11_Ukr_m4185) (Supplementary Table 3).

Aside from providing us with an immense quantity of ancient equid samples, the article has some interesting information in their supplementary section regarding linguistic terminology.

Earliest DOM2 horses

The three earliest DOM2 horses in this article are:

- AC8811_Tur_m2125 - Ahemhoyuk, Central Turkey - 2125 bc

- MOLDA1_Mol_m2063 - Gordinesti II, Northwestern Moldova - 2063 bc

- PRA40_Cze_m2037 - Unetice Culture, Northwestern Czechia - 2057 bc

However, the rise of such profiles in Holubice, Gordinesti II and Acemhöyük before the earliest evidence for chariots supports horseback riding fuelling the initial dispersal of DOM2 horses outside their core region, in line with Mesopotamian iconography during the late third and early second millennia BC. Therefore, a combination of chariots and equestrianism is likely to have spread the DOM2 diaspora in a range of social contexts from urban states to dispersed decentralized societies.

Early Horse riding

I0805 / QLB26 Feature 19614. This 35-45 year-old individual is osteologically and genetically male. The body was buried in NO-SW orientation with the head in the north facing east. Grave goods are scarce and include three silex arrowheads, a few potsherds, and animal bones. A notable observation from the physical anthropological examination is traits at the acetabulum and the femur head suggesting that the individual frequently rode horses.

I6581/HB0031, feature 1561/13: 2456-2146 cal BCE (3825±35 BP, Poz-66185). Theburial contained remains of an adult male (30-35 years old at the death). The deceasedwas positioned on his back, with legs bent at the knees at a sharp angle and stronglybent arms with hands placed on the shoulders. The grave goods comprised three vessels(an ornamented four-footed bowl decorated on the rim and two cups). The bowlcontained poorly preserved animal bones, most likely the remains of food offerings.Multiple palaeopathologies were identified on these skeletal remains. Some lesions maybe evidence of episodes of violence or other circumstances resulting in head injury. Thehigh degree of teeth wear can be caused by frequent clenching and “grinding” affectedby using them in a tool-like manner or bruxism resulted by chronic stress. Other traitsidentified on lower limb bones indicate that the individual most frequently assumed insitting position, with his thighs and shanks in one/almost one plane. Poirier’s facet,often observed in horse riders, is evident. The combination of traits observed on thehumerus may have resulted from using a bow. Genetic data show that he was father ofindividual I6535/HB0032 (feature 1562/13) and individual I6582/HB0040 (feature34/15)

This article also describes the same Bell Beaker male:

This male led an active lifestyle, and the pathologies andnonmetric traits observed on his skeletal remains indicate the repetition of certain activities since juvenility. Lesionson the femora, tibiae, and humeri may, for example, suggest horseback riding in a sitting position with the support of arms behind the back, frequent standing on the toes while reaching for high objects and lengthy episodes of gamehunting with a bow in hand.

Recent Data on the Settlement History and Contact System of the Bell Beaker–Csepel Group - Anna Endrődi The communities of the Csepel group enjoyed a flourishing economy on their large rural settlements. They played a prominent role in the spread of a steppean horse species (Endrődi–Gyulai–Reményi 2008, 252–253). Archaeozoological analyses have demonstrated that horse bones vastly outnumbered the remains of cattle and small ruminants on settlements of the Csepel group. Owing to their mobility, smaller groups appeared as far as Serbia as well. At the Petrovaradin/Pétervárad site, the remains of an Eastern European horse species were found together with the ceramic finds of the Bell Beaker–Csepel group (Koledin 2008, 33–59). Trade contacts can be demonstrated with the Slovakian territory as well.

The Bell Beakers in Hungary were in contact with the Yamnaya groups in the Pannonian basin east of the Tisza river, and intermixed with them to a degree. As the Yamnaya kept horse flocks, this may be a factor as to why horse bones were so frequent there. Unfortunately we don't know if these horses at Csepel were used for anything but meat and/or dairy, and if these horses were traded throughout the beaker horizon.

Although I don't find it a likely proposition, you could argue that the osteological evidence shown could have been the result of another animal being ridden, such as cows. As strange as it may sound it is definitely possible to train cows to be ridden. You can't pull the cowcard with these depictions however:

Then we also have the oldest historical attestation of horseback riding, which came from one of the letters of Zimri-Lin, the ruler of Mari from from 1775 to 1761 BC in which an advisor advises against the king riding horses:

May my lord honor his kingship. You may be the king of the Haneans, but you are also king of the Akkadians. May my lord not ride horses (instead) let him ride either a chariot or kudanu-mule so that he would honor his kingship.

It is interesting that horses still had a sort-of barbarian connotation in those days, but it also suggests that other barbarian peoples in the region were already riding horses and were associated with it to a degree.

Despite this, early horse riding is still considered to be controversial, with many researchers being on the side that horse riding only developed centuries after horses were utilized for traction, some arguing for the iron age being the starting point of horse riding, with cavalries being developed soon after.

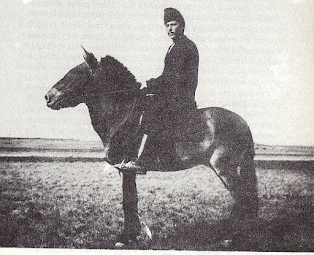

If you subscribe to the takes favoured by archaeologists such as David W. Anthony, horse riding first began as a method to more effectively herd animals (particularly herds of horses) as well as quick transportation of individuals.Without the right gear and equipment, fighting from horseback would not be very effective. The effectiveness of horse riding would be quite limited as well given that saddles were not properly a thing yet, as these seals without saddles would suggest.

If you're on the other isle of the debacle, pictographic evidence of horse riding only shows up in the later bronze age, with those earlier depictions dismissed as "unclear equids", and horse riding only shows up after a long and rich history of using horses for chariots, with the Neo-Assyrian empire being the first historical society to implement horse riding in a significant matter.

Despite being a staunch critic of Anthony's arguments in favour of horse domestication, don't mistake that for Levine being of the opinion that horse riding was an late bronze age/iron age phenomenon.

It is highly improbable, however, that traction horses could have been herded either on foot or from a vehicle. Therefore it seems almost certain, as far as the horse is concerned, that riding would have preceded traction. One interpretation of this evidence is that the horse was first domesticated for traction around the end of the third millennium bc and for riding a little earlier (Khazanov, 1984; Renfrew, 1987; Kuz’mina,1994a,b). However, it is almost certain that horse husbandry must have developed well before its earliest unambiguous manifestations in art and burial ritual.

Marsha Levine - Domestication and early history of the horse

While many have broken "wild" horses before, these were generally in one way or another descendants of domestic horses gone feral. As the current academic consensus has shifted towards "no"for Botai horse riding and domestication, Vaska arose from a population of horses which never went through a similar selection process. Vaska was a special stallion however, as this wasn't apparently mangeable with the other horses from the flock. Perhaps he had GSDMC and ZFPM1 mutations as well? What's more important is that if it was manageable with Przewalski's horses, this also would've been possible with other non-DOM2 horses.

In addition, if horse riding developed from long standing use of horses for traction with chariots and wagons, there really needs to be an explanation as to why horses were selected for mutations which influence back pain prior to 2200 BC, that is before we find evidence that horses could've have been used to pull wagons on the steppes.

Horse skiers?

Donkeys

The second point of interest is that 2700 B.C is not far removed from the domestication of the donkey in general, as this had only occured in the fourth millennium BC. Wagons were also rather a recent invention in this era, with the oldest depiction of wagons and a solid wheel coming from 4th millenium b.c Europe, with contemporary existence of wagons and wheels in the near East. In Egypt there is no evidence for the use of wheels until the later third millenium b.c, and on top of that there is no evidence of donkeys being used to pull wagons in Egypt during this period either.

Thus here we have an example of an equid showing up with bit wear mere centuries after the donkey was domesticated by humans. The usage of bitwear cannot have arisen due to long-standing usage of wagons and tractional animals either, as it was a recent phenomenon in the Near East and had not yet reached Egypt, where the aforementioned donkey originated from.

While I wouldn't use the argument that just because something developed with donkeys that this also must've happened with horses, I do think it is rather important to keep in mind. If donkeys were used for riding/pulling within centuries of their domestication and without a long-standing tradition of using animals for wagon traction, I think it would be remarkable if horses were only ridden more than 2000 years after their domestication, due to long-standing usage of horses for traction, chariots in particular.

The origin of the spoked wheeled chariot

While I earlier covered the if, buts, and maybes regarding early horse riding, as well as horse skiing and donkeys, this section will look at the undisputable usage and spread of the chariots during the bronze age. During the bronze age this modified wagon spread across the world, bringing horses with them.

The spread of the chariot also coincides with one of the most significant events of the bronze age, which was the massive spread of Indo-Iranian peoples across Eurasia, ultimately spreading across giant swathes of land which stretched from Ukraine to Mongolia and Xinjiang, and from as far north as Krasnoyarsk, Siberia all the way into South Asia. All of these territories reached within the bronze age as well.

To get to the origin of the chariot I'm going one step further back in time, roughly around 2200-2100 bc. In these centuries we find the existence of modified wagons which very likely were the direct predecessors of the spoked wheeled chariots. They are often referred to as "proto-chariots", and a distinct feature is that they still had solid wheels.

These proto-chariots were found amongst several peoples of the eastern european steppes. Here are two examples from the Catacomb culture:

Another development is the increased appearance of the horse when compared to the Fatyanovo-Balonovo sites, as well as horse cheek pieces, the same type we later see with the spoked wheeled chariot. These signs indicate a growing importance of the horse in the societies of the Abashevo culture. However, in contrast to their southern steppe neighbours and their descendants, the Abashevo did not use horses for sacrificial purposes during funerals. Perhaps it is during this period that the ancestors of the Sintashta people acquired the DOM2 ancestor of the Sintashta horses.

Due to a combination of factors, including the aftermath of the 4.2 kiloyear event on the dry steppes as well as a growing connection to the regions east and south of them amongst others, these Indo-Iranian tribes, by now better adapted to the dry steppe climate began rapidly expanding across the eurasian steppes, both to the west and east.

Not much after the first spoked wheeled chariots of the Sintashta, do we see the spread of the chariot across Eurasia. Pictographic evidence from Anatolia shows that by the 20th century b.c charioteering had already reached the Ancient Near East. A testament to the mobility of Indo-iranian peoples, in particular merchants, horse-trainers and mercenaries who in all probability were the main facilitators of the spread of chariots in the early phases of the second millenium B.C.

The letters of Zimri-Lin from Mari come into play again. One of these letters, dated to 1762 BC, makes a mention of Maryannu, which was a term later used for an elite class of charioteering warriors of the Mitanni state. Maryannu is derived from Sanskrit word Marya, meaning young warrior or rascal even, and the Hurrian suffix -nu. Interestingly this predates the attestations of a Mitanni state by well over a century, but it also shows that Indo-Iranian elements had worked themselves into the Hurrian societies by then.

In my opinion it couldn't be more fitting that the oldest dated attestation of Indo-Iranian languages comes to us by way of a description of charioteers, likely employed as mercenaries. I think the most likely route would be movements across the tin route established between West and southern Central Asia during the copper and bronze age. If you look at the tin deposit locations in Central Asia, it matches up incredibly well with where you'd expect to find Indo-Aryan speakers in the first half of the second millenium BC. These Indo-Aryan peoples likely tapped into the established trade networks to the west via the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological complex, Jiroft and Helmand cultures.

Perhaps these Maryannu mentioned in Zimri-Lin's letters were responsible for the Indo-Aryan royal names, class titles, deities and toponyms mentioned in context of the Mitanni. Or alternatively it was the case that there were regular movements of young male Indo-Iranian warbands into these regions, maybe as seasonal raiders or seeking employment as mercenaries. It would be a pattern consistent with other Indo-European ethno-linguistic groups such as the Germanic, celtic and Slavic people of antiquity and middle ages.

The Hittites of Anatolia also rather rapidly adopted chariots, and were one of the first to employ them at a grand scale. Hittites also developed new forms, such as lighter chariots with four-spoked wheels which were also capable of carrying three soldiers. At the battle of Kanesh, reportedly more than 5000 charioteers shared between the opposing Hittites and Egyptians were present. A few centuries prior Hittite reports describing Hittite and Hurrian battles would feature numbers such as thirty charioteers versus eighty charioteers.

West of the steppes in Europe do we see the spread charioteering as well, with chariot equipment showing up significantly in the Carpathian Basin, Balkans and Greece. Librado 2021 has a neat little map which showcases the finds of chariot goods during the first quarter of the second millenium BC:

Age of equestrians

Considerable changes in the steppes during this period are shown by the appearance of hoards of bronze objects. There are hoards of two types: familyand founders hoards (Kuz’mina 1966: 98). Family hoards (Brichmulla, Turksib, Sadovoe, Sukuluk, Issyk-Kul’, Shamshi, Tuyuk, etc., Figs. 43, 114) contain various types of used objects, which were family property. The appearance of such hoards reflects the process of property stratification of the late Andronovo tribes. The concealment of hoards in the earth indicates the tense situation in the steppe, more frequent military confrontations, which is proved by the spread of numerous types of new defensive weapons and the appearance of cheek-pieces that were used by mounted warriors. All this is evidence of a uniform process connected with the transition to nomadic cattle-breeding.

Helena Kuzmina - The Origin of Indo-Iranians p.97

But the story is a bit more complex than climatic shifts causing shifts in subsistence economies and conflicts, leading to more mobile communities which then developed and perfect horse riding. This phase of increased mobility is followed by a sudden onset of nomadic equestrians coming out of the greater Altai-Sayan region, which is what established the Scytho-Siberian nomadic complex of the iron age.

As Barry Cunliffe puts it well in his book on the Scythians, In this region you can perfectly track the development of Andronovo-derived agropastoralists into the first classic steppe nomad society through the centuries.

With all these changes came a significant increase in population numbers of the late bronze age pastoral communities of the Alai-Sayan region. In addition a significantly more stratified society was developing in these regions; shifting from a society of chieftains to a society of kings.

Whereas on the western steppes, the environmental changes lead to increased aridity and a significantly decreased population, with the people of the Sabatinovka culture abandoning the dry steppes for the coastal regions and river valleys.

It is no coincidence then that the oldest site following Scythian traditions uncovered so far is in Tuva, and when it comes to the oldest sites with a Scythian character, there is a general east to west distribution. But this spread must've been incredibly rapid rather than a gradual one as there are ancient samples from the 10th century B.C much further to the west whose ancestries reveal their origin from those regions.

These migrants rapidly spread across the steppes and assimilated the previous inhabitants into their newly developed nomadic societies. The ones which settled the Pontic-Caspian steppe came to be known as the Cimmerians, with the Scythians as their eastern neighbours. Saka was the Persian term, and was mostly used to refer to the nomadic groups of Central Asia. The Eastern Scythians escape history for the most part, but groups such as the Yuezhi, Wusun, and Loufan have been associated with the Scythian-style archaeological imprints of western China.

But when it comes to horse riding and cavalry it isn't just all about the Cimmerians and Scythians. In fact when the Cimmerians and Scythians arrived on the scene in the Near East, the Neo-Assyrian empire already had an established cavalry.

The first mention of cavalry tactics employed by the Neo-Assyrian empire came from the reign of Tukulti-Ninurta II, who reigned from 891 to 884 BC. Tukulti-Ninurta II also campaigned in the Zagros mountains and subjugated the newly arrived Iranian populations there such as the Medes and Persians, who were experienced equestrians due to their Iranian heritage. It is likely by their influence, or rather by the need to adapt to their military tactics that the Neo-Assyrian cavalry developed. These tactics were then immediately employed to neighbouring kingdoms such as Elam.

The Neo-Assyrian learned most of their tactics by trial and error. Initially they were not able to effectively pull off horse archery, as their methods initially would require a pair of horsemen, one to hold the reins and one to shoot the bow and arrows. "How many horse riders do the Assyrians need to shoot one arrow? Two. One to hold the reins and another to shoot the arrow" Sounds like a bad Cimmerian joke but it was a reality in Assyrian cavalries for a while.

Decline of genetic diversity in ancient domestic stallions in Europe

Sources

- Levine, Marsha. (1990). Dereivka and the problem of horse domestication. Antiquity. 64. 727-740. 10.1017/S0003598X00078832.

- 2012 Levine, M.A. Domestication of the Horse, in Neil Asher Silberman (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Archaeology,Second Edition. Oxford University Press, USA, 978-0-19-973578-5, pp 15-19.

- Novichikhin, A. & Trifonov, Viktor. (2006). Zoomorphic scepter head from Anapa museum. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia. 26. 80-86. 10.1134/S1563011006020083.

- Wilkin, S., Ventresca Miller, A., Fernandes, R. et al. Dairying enabled Early Bronze Age Yamnaya steppe expansions. Nature 598, 629–633 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03798-4

- Librado, P., Khan, N., Fages, A. et al. The origins and spread of domestic horses from the Western Eurasian steppes. Nature 598, 634–640 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04018-9

- N. Benecke - On the beginning of horse husbandry in the southern Balkan peninsula - The horses from Kirklareli̇-Kanligeçi̇t (Turkish Thrace)

- Endrodi A. - Recent Data on the Settlement History and Contact System of the Bell Beaker–Csepel Group

- Furmanek, Mirosław & Hałuszko, Agata & Mackiewicz, Maksym & Myślecki, Bartosz. (2015). New data for research on the Bell Beaker Culture in Upper Silesia, Poland.

- Chechushkov, I. V., Usmanova, E. R., & Kosintsev, P. A. (2020). Early evidence for horse utilization in the Eurasian steppes and the case of the Novoil’inovskiy 2 Cemetery in Kazakhstan. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 32, 102420. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2020.102420'

- Greenfield, Haskel & Shai, Itzhaq & Greenfield, Tina & Arnold, Elizabeth & Brown, Annie & Eliyahu, Adi & Maeir, Aren. (2018). Earliest evidence for equid bit wear in the ancient Near East: The "ass" from Early Bronze Age Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath, Israel. PLOS ONE. 13. e0196335. 10.1371/journal.pone.0196335.

- Köpp-Junk H. - Wagons and carts and their significance in Ancient Egypt - Lindner, S. (2020). Chariots in the Eurasian Steppe: A Bayesian approach to the emergence of horse-drawn transport in the early second millennium BC. Antiquity, 94(374), 361-380. doi:10.15184/aqy.2020.3

- Harmatta J. - Herodotus, historian of the Cimmerians and the Scythians

- Mednikova, M.; Saprykina, I.; Kichanov, S.; Kozlenko, D. The Reconstruction of a Bronze Battle Axe and Comparison of Inflicted Damage Injuries Using Neutron Tomography, Manufacturing Modeling, and X-ray Microtomography Data. J. Imaging 2020, 6, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging6060045

- TAIL AND MANE OF HORSE FIGURINE - FROM ROSTOVKA - I.V. Kovtun

- Institute of Human Ecology SB RAS, Kemerovo © 2014

- Taylor, W., Cao, J., Fan, W., Ma, X., Hou, Y., Wang, J., . . . Miller, B. (2021). Understanding early horse transport in eastern Eurasia through analysis of equine dentition. Antiquity, 95(384), 1478-1494. doi:10.15184/aqy.2021.146

- Taylor, W.T.T., Barrón-Ortiz, C.I. Rethinking the evidence for early horse domestication at Botai. Sci Rep 11, 7440 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86832-9

- Patrick Wertmann, Dongliang Xu, Irina Elkina, Regine Vogel, Ma'eryamu Yibulayinmu, Pavel E. Tarasov, Donald J. La Rocca, Mayke Wagner. No borders for innovations: A ca. 2700-year-old Assyrian-style leather scale armour in Northwest China, Quaternary International, 2021, ,ISSN 1040-6182, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2021.11.014.

- Barry Cunliffe - The Scythians

- David W. Anthony - The Horse, The Wheel and Language

- Andreĭ Vladimirovich Epimakhov, Ludmila N. Koryakova - The Urals and Western Siberia in the Bronze and Iron Ages

- Helena Kuzmina - The Origin of Indo-Iranians

No comments:

Post a Comment