Click here to read in PDF format!

Ancient Xinjiang is a fascinating place, despite my blog being primarily steppe oriented I keep returning to this particular corner of the world for that very reason. Xinjiang is also one of the few corners of the world that keeps on surprising me in terms of the ancient populations which lived there throughout the ages.

I have been digging into the topic of physical anthropology as it relates to ancient Xinjiang quite a bit recently. When I was in the process of adding a bunch of skulls to my digital collection, I figured I might as well start on a small piece to put on my blog, and as you guessed it, it completely grew out of hand.

This post will not just be about the people of the Tarim Basin, the Xinjiang in the title is there because this blog post will cover peoples from various parts of Xinjiang such as the Pamirs, the Barkol-Yiwu region, the Kunlun and Tian Shan ranges. Some of this material will be based on mummified remains, while other parts will be based on skulls. There will be a lot of material presented, this will likely be the most image-dense post on this blog so far. So if you get squeamish at the sight of dried up corpses or skulls, this may not be the post for you.

I also enlisted the help of the talents at AncestralWhispers, who provided me with several artistic reconstructions of the skulls I had managed to dig up (figuratively), giving you a glimpse of what they could have looked like. These reconstructions were made taking into account the anthropological descriptions and craniometric data of the specimens, and when possible, genetic data. These are stunning, and put a face on the various ancient inhabitants of Xinjiang. AncestralWhispers really are the best in the game. Keep in mind that these reconstructions are artistic interpretations at the licence of the artist themselves rather than coming from some magic orb, so do not let this hamper your own imagination!

Physical anthropology of Xinjiang has been quite discussed in the past due to the sheer amount of amazingly preserved mummies we have. Due to the attested languages in Xinjiang being East Iranian and Tocharian, there has generally been an assumption that the Tarim mummies must have been physical representations of either. As I had explained in an older blog entry, the Tarim Mummies were not a people but a natural phenomenon. The people at Xiaohe, Cherchen and Subeixi were not the same people and thus any discussion whether the tarim mummies were tocharian, Iranian or late mesolithic siberian migrants is a foolish one.

In my opinion it also is the case that the existing assumption that these mummies must have represented either of these ethnolinguistic identities affected the archaeological and anthropological interpretations of academia that pointed towards this assumption. Although authors had stressed that we could not know for certain, they operated quite heavily on those assumptions.

Now that some mysteries have been solved due to genetic studies on these early Tarim mummies, a revision of the anthropological materials in light of the newfound knowledge obtained through ancient DNA will be a step towards a better understanding of the populations of ancient Xinjiang.

I’d suggest to read some of my earlier posts about ancient Xinjiang before this one, as several of the populations featured here had been discussed before:

The Tarim mummies were not a people or a tradition, but a natural phenomenon.

Did the Saka migrate to the Tarim Basin and founded the Kingdom of Khotan?

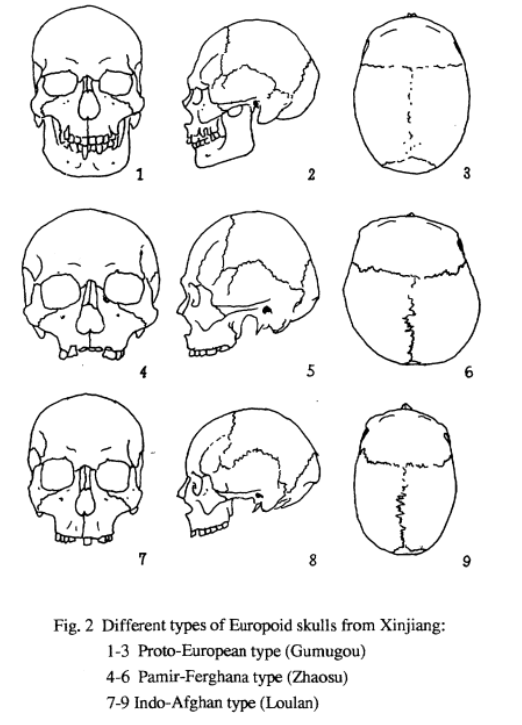

To give a decent introduction, here is how Kangxin Han describes the physical anthropology of the ancient populations of Xinjiang [1]:

At least by the early Bronze Age of this area, Western racial elements with primitive morphological characteristics had entered into the Luobubo (Lopnor) area. Their physical character is close to that of the ancient populations of Central Asia (including Kazakhstan), southern Siberia, and the Volga River drainage basin with the boundaries of the former HAhT Kangxin, "The Study of Ancient Human Skeletons from Xinjiang, China'' Sino-Platonic Papers, 5 1 (November, 1994) USSR. As far as their racial origins are concerned, they have a direct relationship with the ancestors of the analogous Cro Magnon (Homo sapiens) type of late Paleolithic east Europe. Such type of late Homo sapien was also found in the Voronezh region of the Don River drainage. The morphological character of these skulls is apparently similar to that of those skulls from the Gumugou cemetery of the Kongque River, but more primitive than the latter.

Several centuries B.C.E. or a little earlier, other racial elements close to that of the East Mediterranean in physical character entered into the western part of Xinjiang from the Central Asian region of the former USSR. Their movement was from west to east (Xiangbaobao, Tashkurgan, Shanpula-Luopu, Loulan cemeteries). In other words, some of them gradually moved along the southern margin of the Tarim Basin to the Lopnor area and converged with the existing population in the region. This may shed some light on the origins of racial variation in the Loulan kingdom. In addition, it is also possible that some Mediterranean elements crossed to the Tian Mountain region along the northern margin of the Tarim Basin and mixed with the previous population (for instance, as in the Alagou cemetery). It is helpful for understanding the inferences drawn above that the human bones discovered in the Neolithic graves of the Central Asia region of the former USSR (such as Anau of Turkmenistan about 6000-5000 years B.P.) belong to the Mediterranean racial type and the ancient Saka bones from the south and southeast parts of the former USSR (the Parnirs, about 6 centuries B.C.E.), which are adjacent to Xinjiang, belong to the same racial type. All the anthropological materials mentioned above seem to indicate that the opening of the ancient "Silk Road" from Xinjiang to Central Asia supported an eastward migration of the early Mediterranean population of Central Asia across the Pamir plateau (Fig. 3).

Several centuries B.C.E., or perhaps earlier, some Western racial elements (for example, shortened and high cranial vaults) emerged in the upper reaches of the Yili River and Tarim Mountains (for instance, Zhaosu and Alagou cemeteries). How did this racial element form? It is not obvious. Some scientists believe that they developed from the Proto-European with a change in cranial morphology to a more shortened vault, with the addition of some Mongoloid features. But it is not certain what Mongoloid elements were involved. Some scholars have argued that it is the result of a mixture of Proto-European and Mediterranean racial elements. How far these people spread into Xinjiang and the extent of the distribution of this racial element are the subject of continued research.

The first description of a racial type was that of the Proto-Europoids, which mainly is based on the appearance of upper palaeolithic skulls in Europe. Europoid and Caucasoid are pretty much just synonyms by the way, and you can consider this the anthropological classification of populations we refer to as West Eurasian in genetic terms. I wonder which late palaeolithic eastern european specimens Han was referring to, perhaps the famed Sunghir man?

The second type is an east mediterranean racial type. Other names used for this category, particularly in the contexts of Central Asia are Trans-Caspian and Indo-Afghan. This generally refers to caucasoid populations with relatively gracile skulls, dolichocephalic indices and leptomorphic faces. West Asian populations. Early neolithic agricultural populations from the Near East were of such origins, and you can think of this type as “West Asian” (although a significant presence in Neolithic Europe and modern day southern Europe). Here are some examples from eneolithic Geoksyur coming from Chagylly depe and Chakmakly depe, which Han mentioned in his description:

By the iron age we are definitely not dealing with pure representatives such as those at Geoksyur. Their societies had been upended by the Andronovo migrations into southern Central Asia from further north, and by the iron age you had Iranian peoples with ancestry from both of these populations in similar ratios.

This third type is commonly called Pamir-Ferghana, also known as the Central Asian interfluve race is an anthropological type based on the cranial shape commonly seen amongst lowland Tajiks and Uzbeks. Sometimes these racial types get peculiar names, one I personally find hilarious is the so-called “Andronovo turanid” type which has no resemblance to Andronovo populations at all. The Pamir part in Pamir-Ferghana is a strange addition because from a cranial perspective Pamiris do not conform to the Pamir-Ferghana type at all, being primarily a narrow-faced dolichocephalic population. Race of the Central Asian interfluve however is too much of a mouthful for me, so despite my grievances with the term I will continue using Pamir-Ferghana.

Another point worth mentioning is that this “racial type” in the modern day and age is connected to populations in southern Central Asia, however in the context of the iron age we find populations with key characteristics of Pamir-Ferghana type such as meso-brachycephalic skulls with shortened and high cranial vaults in the communities of the iron age Scytho-Siberian complex. Southern Central Asian populations during this period were primarily of the Trans-Caspian/Indo-Afghan described earlier.

The similarities in cranial forms between the Scytho-Siberians and modern Pamir-Ferghanans are most likely simply due to chance rather than a close genetic relation or even a genetic similarity between Scytho-Siberians and Uzbeks/lowland Tajiks. Although east eurasian ancestry is common in both this is unlikely a source because you can find Andronovo skulls conforming to this type already.

The remains of the Karasuk culture had been described as pristinely Pamir-Ferghana which explains the significant expression amongst iron age Scythian populations. Here are two examples from different parts of the Scythian horizon conforming to this type. The first one is a Sarmatian male from the Kazybaba burial ground in the Ustyurt plateau, representing a southwards intrusion of Sarmatians from the Ural-Caspian region. You might see this population featured in a future post. The second example is a Saka-Wusun period male from the Kapchagay III burial of Central-Eastern Kazakhstan.

When it comes to the “western” peoples of ancient Xinjiang, most authors operate under this anthropological framework. Keep in mind however that ancient DNA shows that Xinjiang has been a melting pot of various ancestries, both of west and east eurasian extraction, since the bronze age and thus having a “europoid” or “mongoloid” cranium does not have to mean an purely western or eastern genetic profile. Within populations of the same genetic profile you can have different cranial types as well, so one has to be careful equating cranial types directly to genetic ancestries. There definitely is a correlation between the two however, and people who say otherwise simply are mistaken.

Bronze age

Xiaohe-Gumugou culture

The people of the Xiaohe-Gumugou culture, also known as the Qawrighul culture or Ayala Mazar-Xiaohe culture depending on the authors were the early bronze age inhabitants of the Tarim Basin, known for some of the famous mummies such as the Loulan beauty, the Xiaohe princess as well as various others from sites such as Gumugou, Xiaohe, Beifang Mudi etc.

The anthropological description of these populations was that of a predominantly caucasoid, proto-europoid population, although some anthropologists also noticed signs of East Asian features. Early inhabitants of the Pontic-Caspian steppe were quite often described as being Proto-Europoid and as you can see, anthropologically it was considered these groups to have a relation with one another. This had been taken as evidence of an Afanasievo origin of the early Tarim basin cultures, the Afanasievo also being a prime candidate for the progenitors of the Tocharian language.

To sum up, these skulls have definite Western racial characteristics. The homogeneity between individuals also is clear. In consideration of the synthetic character mentioned above, they seem to show some primitive features which have collectively been called "Proto-European type" by some anthropologists of the former USSR in the past Racially, they are close to the populations of the Bronze Age of southern Siberia, Kazakhstan, Central Asia, and even the grassland areas of the lower reaches of the Volga River- (Han Kangxin, 1 986b).

All of that changed in late 2020, when ancient DNA from bronze age sites of the Tarim Basin were published. Instead of looking at Afanasievo-derived people mixed with Siberians, Central Asians, or Upper Yellow River populations we found a highly drifted relict population, derived mostly of Ancient North Eurasian ancestry with minor Northeast Asian ancestry.

I remember it quite well, the data was available months before the actual article did and we had to puzzle what went on. Looking at the IDs of the samples I quickly realised that we were dealing with samples from Xiaohe and Gumugou, and later I figured that from an archaeological perspective these came from the same layers as earlier genetic reports on the Xiaohe samples,

In case you don’t have a clue what I’m referring to, go and read this:

The genomic origins of the Bronze Age Tarim Basin mummies | Nature

Gumugou

Gumugou, also known as Qäwrighul is one of the main bronze age sites of Xinjiang, particularly for the purpose of physical anthropology. The descriptions of the bronze age peoples of Xinjiang I posted came from the dataset at Gumugou. Ironically finding actual physical remains from Gumugou on the other hand was a very difficult task, one which I had not been able to successfully pull off. That is until Yunyun Yang came to the rescue and sent me a copy of Han’s article about Gumugou, which means that I will be able to present them after all. Shoutout to Mrs. Yang!

Apparently at the Gumugulo site there were two types of burials. One of the burial styles utilized was similar to those at other sites such as the Xiaohe cemetery, where the peoples were buried in boat-shaped coffins. The main group of burials at Gumugou were the Type II burials, which had boat-shaped coffins similar to Xiaohe. The one genome from Gumugou apparently comes from such wooden coffin burials. The other style was typified by the sun-radiating spokes, the people buried in these graves were all male. Yang called these Type I burials [2].

From burials, the Gumugou cemetery had heterogeneous burials, such as type I the sun-radiating-spokes burial pattern and type II the normal burial pattern. From a morphological view, skulls from burial type I, sunradiating-spokes burial pattern, are more similar to Andronovo people, and skulls from burial type II, the normal burial pattern, are more similar to Afanasievo people (Han 1986)

The skulls of the burial type I have been described as approximating Andronovo more than the type II burial remains, being more similar to “Afanasievo craniums”, and Yang suggests that it is possible these were Andronovo derived or at least influenced by them.

Looking at the burial map you can see how the burials could be of another population which came to an already existing burial ground and added their own graves to it. However, it can also be interpreted as a development in traditions within the same population, with those type I burials occurring slightly later than the main burial type burials. Given that anthropologically Afanasievo-like individuals turned out to be a completely different population, it might be the same with the Andronovo-like individuals.

Of the skulls presented below, number 1 to 6 are from these type I burials. These are the skulls described as approximating the Andronovo peoples in cranial shape. All of these six skulls belonged to males. The skulls numbered 7 to 18 are from the more common type II burials and contained both male and female specimens [3]. There is some further information below the images of the skulls giving context and descriptions of the specimens, translations provided through translation services although I had to make some changes here and there, apologies if it reads a bit awkwardly.

Description type II:

No. 1 / 75LQ2M1:

Complete skull, 25-30 years old male individual. The skull is large, of medium length, very tall, narrow, with a moderate slope behind the forehead. The brow arches are thick, the glabella is strongly protruding (grade 6), and the root of the nose is deeply depressed. The surface is between the high, the high and the low, and the surface is wide, which is between the middle and the middle. The upper and lower faces are strongly prominent in the horizontal direction, and the middle and small areas are prominent in the lateral direction. The cheekbones are broad, the nose is low, the orbit is low, the nasal protrusion is prominent, and the canine fossa is shallow. The top of the skull is highly arched, and the posterior occiput is round and not prominent. The dorsum of the nose is strongly curved, and the nasal bone is very short. Upper incisors are weakly spade-shaped. Anthropological type is close to the primitive European species, and also somewhat similar to the skulls of the Cro-Magnons in the late Paleolithic (Plate 17, 1-3).

No. 2 / 75LQ2M6:

Complete skull (missing jaw), 50-60-year-old male. The cranial shape is long and narrow, and the high absolute value is large, which is an orthocranial shape. The forehead slope is weak, the brow arch (grade 3.5) and the glabella are moderate. The nasal bone is short, the dorsal of the nose is obviously curved, and the protrusion is medium. Nose, low orbit. The upper horizontal protrusion is small, the lower protrusion is obvious, and the lateral protrusion is weak. The cheekbones are narrow and the canine fossa is deep. The top of the skull is obviously arched, and the posterior occiput is round. The top hole-herringbone dot area is relatively flat. Anthropological type one is close to the Andronovo type of the primitive European race (Plate 17, 4-6).

No. 3 / 75LQM7:

relatively complete skull, larger than 55-year-old male. The cranial shape is long mesocranial and narrow cranial, the cranial height is very high, and it is a high cranial type. The frontal slope is weak, the brow arch and glabella (grade 5) are strongly prominent, and the nasion is deeply depressed. The nasal bone is broad and very short, the dorsum of the nose is obviously curved, and the middle of the nasal protrusion is weak. The face is low and wide, with a strong to medium protrusion in the horizontal direction on the upper side, a large protrusion on the lower side, and weak protrusion in the lateral direction. The canine fossa is medium deep, the orbit is low, and the nose is broad. The top of the skull is more arched, and the posterior occiput is more rounded. Anthropological type 1 is closer to the Andronovo type of the primitive European race (Plate 17, 7-9).

No. 4 / 75LQM8

Complete skull, 45-55 years old male. The cranium is shorter and wider, between the middle and brachycephalic types. low cranial height, Orthocephalic type. The forehead is obviously low-sloping, the brow arch and glabella (grade 5.5) are strongly protruding, and the root of the nose is deeply depressed. Nose shape, the dorsum of the nose is obviously curved, and the nasal protrusion is medium. The face is low and moderately wide, the frontal plane has a weak protrusion in the horizontal direction, the maxillofacial protrusion is moderate, and the lateral protrusion is moderately weak. Canine fossa depth weak-medium, middle-high orbital. The top of the skull is highly arched, the posterior occiput is not protruding, and the parietal foramen and herringbone point area are relatively flat. Anthropological type is close to the European race Andronovo type, with a low skull and a sloping forehead similar to the characteristics of the Afanasievo type (Plate 18, 1–3).

NO. 5/79LQM9:

Broken and incomplete skull (skull base, lower half of occipital bone and left zygomatic defect), older than 55 years old male. Medium-long skull, medium-sloping forehead, moderately developed glabella (grade 3) and brow arch, moderately depressed nasion. The middle length of the nasal bone is very short, the upper part is narrow, and the dorsum of the nose is curved. The nasal protrusion is small, the nose. The surface is low and wide, the upper horizontal direction protrudes weakly, and the orbit is low. narrow cheekbones, cranial More arched, more rounded posterior occiput. The anthropological type is a European race, which may be close to the Andronovo type (Plate 18, 8, 9).

No 6. 79LQ2M10:

Relatively complete skull (the lower part of the nasal bone and a small piece below the left infraorbital foramen are missing), older than 55 years old male. Between the long one cranial type, and between the high cranial high school and the high cranial type, it is orthodox cranial type. Mid-slope forehead, thick brow arch, prominent glabella (grade 5), deep nasion depression. The nasal bone is broad and strongly protruding, the dorsum of the nose is obviously curved, and the nose shape is between a broad nose shape. The height and width of the face are between medium and large, the upper part is protruding in the horizontal direction and the middle is weak, the lower part is protruding between the large and the medium, and the lateral direction is protruding and weak. Canine fossa superficial to medium, low orbital type. The top of the skull is more arched, and the posterior occiput is round. Anthropological type - European race is close to Andronovo type (Plate 18, 4, 5).

Description Type I:

NO. 7 / 79LQ2M25

complete skull, older than 55 years old male. Medium-long cranial type, medium cranial type with wide skull, low skull height, It is orthocephalic. The forehead slope is more than moderate, the glabellar (grade 3) and brow protrusion are weak, and the nasal root depression is moderate. The bridge of the nose is obviously curved near the root of the nose, the nasal protrusion is larger than medium, and the nose is shaped. The face is relatively low and wide, and it is a wide face. The upper and lower horizontal protrusions of the face are weak, and the lateral protrusions are small to medium. The canine fossa is superficial and the orbit is low. The top of the skull is relatively arched, and the posterior occiput is moderately prominent. Anthropological Type I The European race is relatively close to the Afanasievo type (Plate 18, 6, 7).

NO.8(79 LQzM28)

Complete skull, male about 35-55 years old. The cranial shape is long and narrow, and the cranial height is medium, which is an orthodox cranial shape.The forehead slope is greater than medium, the degree of glabellar protrusion is less than medium, and the brow arch is prominent. Low profile, of medium width, with moderate horizontal projection above, greater than medium projection below, and moderate projection laterally. The base of the nose is moderately depressed, the nose protrudes obviously, the bridge of the nose is concave, and the nose is broad. Cheekbones broad, canine sockets weak, orbit low. The top of the skull is relatively arched, and the posterior occiput is moderately prominent. The Anthropological Types is European Race, similar to the Afanasievo type (plate ten nine, 1-3).

NO. 9 (79LQM29)

Complete skull, older than 55-year-old male. The cranial shape is long and narrow, the cranial height is medium, and it is orthocephalic. The forehead is strongly receding, the glabella (grade 5.5) and the brow arch are strongly prominent, and the root of the nose is deeply depressed. The nasal bone is prominently protruding, and the dorsum of the nose is significantly curved. The face width and face height are medium, which is the middle face type. The upper and lower faces protrude strongly horizontally, and moderately protrude laterally. The canine fossa is weak, the orbit is low, and the nose is narrow. The top of the skull is arched, the posterior occiput is round, and the top hole and herringbone point area are flat. Anthropological types—European races, and Afanasievo type is close (Plate 19, 4-6).

NO. 10 (79LQM30:B)

Broken skull, male aged 45-50. The cranial shape is short, the forehead is oblique, the brow arch and glabella (grade 3 strong) have well-developed protrusions, and the root of the nose is deeply depressed. Anthropological type - European race.

NO.11 (79LQM31)

Complete skull, 35-40 years old male. Long and high-skull type. Mid-slope forehead, brow arch and glabella (grade 4.5) are prominent, and nasal root depression is deep. The nasal bone is strongly protruding, the bridge of the nose is obviously concave, and the nose is narrow. The surface is high, the surface width is moderately strong, and it is the middle surface type. Strong horizontal projection above and below, moderate projection laterally. The canine fossa is not visible, and the orbit is low. The top of the skull is arched, and the posterior occipital is round and somewhat prominent. The top hole is relatively flat between the herringbone dots. Anthropological type-European race is close to Afanasievo type (Plate 19, 7-9).

NO.12 (79LQM3)

Complete skull, female aged 25-30. Between the middle and long types (the lower limit of the middle size), the cranial height is medium, and it is the orthocranial type. Mid-slope, weak brow and glabella (grade 2) protrusions, shallow nasion depression. The nasal protrusion is prominent, the bridge of the nose is concave, and the nose is of medium width. The height and face width are medium, which is the upper middle type. The upper and lower faces protrude strongly horizontally and moderately protrude laterally. Cheekbones wide, canine fossa shallow to medium deep, low orbital. The top of the skull is rounded, and the posterior occiput is slightly flattened to the right. Anthropological Type-European Race, Morphology between Andronovo type and Afanasievo type.

NO. 13 (79LQM?)

Relatively complete skull (incomplete lower nasal bone), female aged 35-40. Long skull type, tall. The forehead is slanted and large,the glabella and brow arches are weak, and the nasion is shallow. The nasal protrusion is medium, the dorsum of the nose is concave at the base of the nose, and the nose shape is broad. The face is low and medium wide, which is a wider face type. The horizontal and lateral directions of the face project between medium and large. Cheekbones are broad and prominent, canine fossa weak, orbit low. The top of the skull is more arched, and the posterior occiput is more prominent. The anthropological type, the European race, may be somewhat similar to the Afanasievo type (Plate 20, 7, 8).

NO.14 (79LQM11)

Complete skull, female between 35-55 years old. Skull is small, long skull type, high and low, is low skull type. Straight forehead, brow and brow prominence very weak, no nasion depression. The nasal bone is very wide, the nasal protrusion is smaller than medium, the nasal bridge is concave, and the nose is broad. The surface is low and narrow, the horizontal protrusion is between medium and small, and the lateral sudden change is small. The cheekbones are narrow, the canine fossa is deep, and the orbit is low. The top of the skull is relatively

arched, the posterior occiput is obviously protruding, and the space between the top hole and the herringbone point is slightly flat. Anthropological type - European race may be close to the

Afanasievo type.

NO. 15 (79LQM12)

Complete skull, female about 55 years old. The cranial shape is long and narrow, and the cranial high school is between high and high, which is an orthodox cranial shape. Mid-slope forehead, weak glabellar and brow arch protrusions, shallow nasion depression. The nasal protrusion is obvious, between the middle and broad noses, and the nasal bridge is concave. The height and width of the face are medium, the horizontal direction of the upper part is weak, the lower part is between the middle and large, and the side is between the small and the middle. Middle-low Orbital type (high on the left and low on the right), the canine fossa is weak and medium. The top of the skull is moderately arched, and the posterior occiput is more prominent. Anthropological type-European race, probably close to Afanasievo type (Plate 20, 9).

NO.16 (79LQM17)

Complete skull, older than 55 years old female. Long and narrow, high skull, high skull type. Moderately sloping forehead, weak brow arch and glabella, moderate nasion depression. The nasal protrusion is medium, the nasal bone is short, the nasal dorsum is concave, and the nose is shaped. Low-faced and moderately wide, with strong horizontal projections above and below and weak lateral projections. The canine fossa is larger than medium deep, the zygoma is narrow, and the orbit is low. The top of the skull is particularly arched, the back occiput is round, and the top hole is flat with a herringbone point. Anthropological type—European race, probably close to the Afanasievo type (Plate 20, 3, 4).

NO.17 (79LQzM26)

Incomplete skull (incomplete occipital and skull base), 40-50-year-old female. Skull is small, long and narrow skull shape, and skull height is little. Straight forehead, brow arch and glabellar protrusion are not obvious. The root of the nose is flat, the nasal protrusion is small, and the bridge of the nose is concave. Face low, less than medium wide, between medium and broad. The top is moderately prominent horizontally, the bottom is less than medium, and the lateral projection is weak. Zygomatic bone narrow, canine fossa deep, high orbital type. The top of the skull is less arched. A small amount of hair is preserved on the forehead of the skull, which is light brown with a small amount of white hair. Anthropological type-European race.

NO. 18 (79LQzM34)

Relatively complete skull (nasal bone and left mandibular branch broken), 20-25-year-old female. Long and narrow cranial type, high cranial height, between normal and high cranial type. Medium sloping forehead, weak brow arch, smaller than medium glabellar protrusion, medium nasion depression. The face is medium to high in height,and the face width is relatively large, which is between the middle face and the middle face. The facial protrusion is obvious in the horizontal direction, the lateral protrusion is moderate, and the upper jaw is more obvious. Medium-high orbital shape, medium-deep canine fossa. The top of the skull is more arched, and the posterior occiput is more rounded. The top hole is flat between the herringbone dots. The anthropological type, the European race, may be close to the Afanasian type (Plate 20, 5, 6). 20-25 year old female. Relatively complete skull, long and narrow cranial height. Anthropological type is European, close to Afanasievo.

As can be seen, the first group is more commonly described as approximating the Andronovo, and the second group as approximating the Afanasievo. However in both groups there were cases where the skull was described as closer to the other or being in between the two morphologically.

Due to genome wide analyses we now know that the “Afanasievo” group were actually ANE-rich relict populations, so what about the “Andronovo” type then? I suspect these were the same type of people as the other group of Gumugou. They share many similar features in terms of their cranial shape and facial morphology. The differentiation between the two groups mainly seems to be that the second group had slightly more narrow skulls, but these also had a larger sample set and two genders. Physically I don’t think they particularly look very Andronovo-like either, at least not when compared to other populations. According to AncestralWhispers their measurements are more similar to those of Khvalynsk for instance.

It may be that the first group had been in contact with other populations present in Xinjiang and had picked up some genomic ancestry not seen in the first group together with new cultural influences affecting their burial rites, but I kind of doubt that. The burial rites of these two groups differ, but they share a lot with each other, more than they do with the Andronovo burial customs themselves. Hopefully ancient DNA research projects in the future will either confirm or debunk my speculations.

Loulan

Loulan or Kroran was the name of an ancient city and kingdom around the now largely dried up Lop Nur lake. Around this area you also have archaeological sites and cemeteries, no surprise given that the Salt Lake must have been a refreshing source of life in an otherwise arid desert region.

In the 1980s a particularly well-preserved mummy was discovered, dubbed ‘The sleeping beauty of Loulan’. She ended up being one of the most famous of the ancient mummies of Xinjiang.

This is the mummy in her original state:

The beauty of Loulan would have been in her 40s/50s when she passed away, and she likely would have suffered from lung disease due to the ingestion of sand.

This is another famous mummy from Loulan, often conflated or referred to as the beauty of Loulan as well. However this is a different mummy, excavated in 2005. She would have been in her 20s when she passed away.

Beyond the sleeping beauty of Loulan, I came across a pair of skulls from a 1929 article by Arthur Keith, which might be one of the oldest physical anthropology works relating to ancient Xinjiang. The famed Aurel Stein was responsible for the discovery of these craniums, and assumed these were from the common era [4].

A few miles to the east of Ying-pan-farther down the dried bed of the Kuruk- darya and still on the ancient Chinese route, there was another cemetery, from which Sir Aurel Stein brought away two skulls-both of men-one marked " L.T. 03)" (No. 1 of my tabulated lists-because it is the most representative of the four male skulls), the other marked " L.S. 2. 07 " (No. 2 of my lists). The position of this cemetery is shown in Text-fig. 1. Of these two skulls Sir Aurel Stein has written: " From burial places of the indigenous inhabitants of ancient Loulan in the now waterless Lop Desert. Period probably 2nd-3rd centuries A.D."

Now if these are from the 2nd-3rd century AD then they clearly shouldn’t belong in this particular section, but I think they are remains of the bronze age population of the Tarim Basin. The first thing which tipped me off is that there was quite a resemblance between the two skulls presented and the Gumugou skulls, as well as a resemblance to skulls from the Botai culture and some Altai neolithic craniums.

Reading Aurel Stein’s descriptions of his excavations in the Loulan area, the remains of the people he found in a cemetery near the Mesa were described as interred in wooden coffins, wearing felt caps with goods such as weaved grass baskets, bundled twigs and jade ornaments either found around or in the graves [5]. Sounds familiar?

“In spite of the traffic and trade that Chinese enterprise had brought to the jungles and marshes where they hunted, fished, and grazed their herds, they had evidently clung to their time-honoured ways and retained their distinct, if primitive, civilization.”

Stein provided a photograph of one of the mummies he came across on the mesa near Loulan:

Which pretty much confirms to me that the people he described were the early bronze age inhabitants of Xinjiang. Although coming from a site about 200 km away, the Loulan skulls were held to belong to the same type of people as discussed above, which I think is a solid confirmation that the skulls provided do not just simply resemble those of Gumugou, but belonged to the same population.

Now about those skulls, Keith presented two male craniums in his article of which you can see the drawings below, I also added the descriptions to them.

L.T. 03

The first Loulan skull (L.T. 03) is depicted in P1. XVI-in all four aspects, so that a full description is not necessary. The points of resemblance to the head from Turfan are numerous and intimate. The man's age was probably between 30-40 years; the sutures are unobliterated and the molar teeth are worn only to the depths of their cusps. The highest point of the vertex lies 40 mm. behind the bregma; the parietals slope backwards and downwards to end in an occipital region, which is not vertical as in the Ying-pan skull, but is cap-like. The form in profile is that we meet with in dolichocephalic skulls; the maximum length- glabello-occipital-is 181 mm.; its maximum width-at the squamo-parietal junction-is 135 mm.; the width is 75 per cent. of the length. The height-basi- bregmatic-is 138 mm., and the auricular (bregmatic) height 118 mm., but the highest point of the crown is 5 mm. more-123 mm. The height is great compared to the length and breadth. The cranial capacity, taken directly, is only 1230 c.c. The sides of the skull are flat and nearly vertical, the width below the parietal eminences being only 2 mm. less than lower down. The roof is ridged, the parietals sloping upwards to meet at the sagittal suture. The neck was of moderate strength, the bimastoid width being 129 mm.; the inion lies 67 mm. behind the mid-point of a line joining the anterior margins of the mastoid processes. The frontal bone, at its widest, measures 121 mm. ; at its narrowest (biminimal width), 98 mm.

When we turn to the facial aspect of this skull we find the same European-like conformation of the forehead as in the Turfan head; both supraciliary and supra- orbital processes are prominent and sharply demarcated; the outer ends of the supra-orbital processes project laterally, the width between their outer ends being 112 mm., giving an unmongolian aspect to the lower forehead. The total height or length of the face is 102 mm.-a short face; its greatest width-bizygomatic, 128 mm.-also small. The length of the upper face-naso- alveolar is 64-mm., and the width between the lower ends of the malo-maxillary sutures 100 mm., which is large compared with the bizygomatic width. The nose, somewhat damaged, is short, its height being 46 mm., its width 26 mm.-a relatively wide nose. The nasal spine runs forward, jib-like, and the lower margin of the aperture shows no fossee, but has a well-marked border continued from the wings of the spine to the lateral margin. There is no subnasal prognathism; the incisors meet in an edge-to-edge bite; the chin is well developed, lying 4 mm. in front of the lower alveolar point. The depth of the symphysis is 30 mm.; the angles of the lower jaw are not prominent, having a bigonial width of 96 mm. The width of the ascending ramus of the jaw is 34 mm. All the teeth are sound; the surfaces of the molar teeth have been worn flat and even by chewing. The dental arcade is well formed; its bi-canine width is 42 mm., the bi-molar width 65 mm., its antero- posterior (median) length 53 mm., the depth of the palatal vault 18 mm.-8 mm. less than in the long-faced man of Ying-pan. Were it not for the guidance given by the Turfan head, the craniologist might have doubted the Mongoloid affinities of the man to whom this skull belonged.

L.S. 2. 07

"The second skull from the Loulan cemetery, marked " L.S. 2.07 " (No. 2 of my lists), needs only a brief description; it is so like to the one just described. Its detailed measurements will be found in the tabulated lists; its four aspects are depicted in P1. XVII. The skull is that of a man about 45 years of age; the posterior half of the sagittal suture is obliterated. The molars are worn so as to expose a complete field of dentine on their chewing-sur-faces. The roof, as in the last, slopes upwards to the median line; the sides draw in as they rise to the parietal eminences -the lower or greatest width being 139 mm.; the upper parietal being 128 mm. The greatest length-glabello-occipital-is only 174 mm.; the width is 79 9 per cent. of the length-the skull thus rising in its diameters almost to the brachy- cephalic class. Yet we see nothing of the occipital flattening usually found in brachycephalic skulls-its contour in profile is dolichocephalic. The roof is re- latively high; the basi-bregmatic height is 138 mm.; the bregma lies 115 mm. above the Frankfort plane; the highest point of the vault-40 mm. behind the bregma-118 mm. The cranial capacity is 1265 c.c., being a small amount. The facial conformation is that of the last specimen, only the bizygomatic width is greater, the subnasal prognathism a little more marked, but the chin is particularly well formed and prominent-a very unmongolian feature. The teeth are all sound and the dental arcade well formed.”

I am under the impression that Keith called any population with a considerable amount of East Asian ancestry as Mongoloid, as he also called Osmanli Turks Mongoloid when these certainly were of significantly mixed character. But it shows he was aware of something that took nearly a full century to be proven by ancient DNA, that these populations had East Asian ancestry and were not purely of western extraction.

Another famed cemetery to the west of Lop Nur is the Xiaohe or Small River cemetery, also known as Ordek’s necropolis. A large cemetery with over 300 tombs, Xiaohe was used during the bronze age by the native populations of the Tarim Basin. Due to the sheer materials and graves of Xiaohe it is one of the defining archaeological sites of the bronze age Xiaohe-Gumugou culture.

Xiaohe is known for the large amount of well-preserved mummified remains of people, with over thirty such remains having been uncovered. One famous example is the Xiaohe princess from grave M11 [6], which was uncovered in 2002:

Another Xiaohe mummy, said to be one of the oldest ones uncovered from the site:

This is one of the males at Xiaohe from burial M24:

This archaeological site, also known as the northern cemetery near the Keriya river, is deep in the western parts of the Tarim Basin. Undoubtedly the reason why these people lived so far inlands was due to the nearby Keriya river. This location is a considerable distance from the other sites such as Xiaohe and Gumugou, situated about 600 kilometres away and shows the rather vast distribution of such a bottlenecked small population during the bronze age. First excavated in 2005, this burial complex revealed some exceptionally preserved mummies. One of these mummies was that of a woman with light blonde hair. The material culture at Ayala Mazar shares the same fertility cult rituals as present at Xiaohe. [7]

Stature and phenotypes

I had mentioned the issues where mummies spanning thousands of years are assumed to have belonged to a singular population. Another issue is inaccurate reports on their physical stature flying about. You will often hear about 2 meter tall giant mummies of the Taklamakan. Cherchen man has sometimes been described as being over 190 cm tall, but in reality more like 174 cm at best. Yingpan man is actually an example of a tall mummy, being above 190 cm. You also have reports of giant skeletons at Kungang above two meters, which I have not been able to verify in any report. The Cherchen man is from the iron age, as are the Kungang tombs and the Yingpan man is from the 4th century AD, hardly relevant for the early inhabitants of the Tarim Basin.

What about the bronze age inhabitants of the Tarim Basin? Unfortunately the information regarding their stature is quite limited. There are some cases where the heights of the skeletons are reported, but never in a manner where measurements or regression formulas used were provided. So you just have to take their word and hope that the height measurement was accurate.

The male of burial M24 at Xiaohes was described as being 164 centimeters tall. At Xiaohe another stature estimation was given for the female M13 at 150 centimeters. The sleeping beauty of Loulan was of similar height, around 152-155 centimeters. However, the other female mummy from Loulan was described around 165 cm in the video I linked earlier, slightly taller than the M24 male.

It is hard to gauge what their average heights would have been based on this limited data. Globally the difference in male to female stature is about 7%. With said percentage the female equivalent height of M24 would be 153 cm, and the male equivalent for M13 would be 160.5 cm. The male equivalent of the Loulan beauty would be 163 - 166 cm. The average converted female-to-male height would then be around 163.1 cm. Naturally this too is a bit problematic because dimorphism varies in populations and it may be that the height difference between the two genders of this population was not around 7%. However the numbers do match up quite well with one another so despite the limited sample size and questionable measurements this might be fairly in line with their stature. The second Loulan shifts the situation though as she was 1 cm taller than the male from M24. Her converted female-to-male-height would have been 176.55.

Here are these various heights listed in a table, the bolded numbers are actual heights and the ones with (c) are converted figures.

The average including all of these would be 166 for the men and 155 for the women. The second Loulan sample seems a bit of an outlier however, particularly because the rest all have heights quite consistent with one another. It might be that the height estimation was not accurate, or it may be that in a larger sampleset we’d see a larger amount conform to the other samples. Excluding these gives 163 cm and 152 cm.

A male height around 163-166 cm and a female height around 152-155 cm is not particularly tall for that time period, and is quite short when compared to contemporaries such as Yamnaya or the Kumsay peoples. Given the harsh climates they lived in, they probably did not maximise their height potential. At first you’d think that with the livestock, dairy and riverine resources from a dietary perspective these people would be well off, but they regularly would have had to resort to hunting vultures, badgers, snakes and lizards to sustain themselves, undoubtedly as their late hunter-gatherer ancestors near the Taklamakan did also. Many of these remains had sand in their lungs and as well as other signs of health complications.

Due to their peculiar geographic location this population had quite the isolation, this can be seen through their very limited haplogroups and their runs of homozygosity (ROH) being very high, comparable to first-degree incest. This genetic isolation has led to some rather unique genetic selection events, and this population can be seen as a case study of this phenomenon.

In most west eurasian populations, when it comes to depigmentation on the skin there has been quite the selection on the snps rs1426654 and rs16891982. Rs1426654 was present in various neolithic populations from the middle east, as well as hunter-gatherers from Eastern Europe. In West-Siberia and Central Asia, hunter-gatherer populations also seemed to have had it. This snp was not present amongst the peoples of the Tarim Basin. Likewise rs16891982 was missing as well. It could be that due to a heavy bottleneck event that these peoples “lost” these snps if they were heterogeneously present in their ancestral population, but I think a likelier explanation is that their ancestors genetically separated prior to the selective sweeps on these snps which occurred in those populations.

What they do seemed to have were pigmentation-related snps such as rs1800404 of the OCA2 gene, and rs885479 - SNPedia on the M1Cr gene.This suggests they had independent selection events for snps related to depigmentation on the skin than the other ANE-rich populations. It is hard to be certain what their skin colour would have been like, and to which degrees these peoples would have tanned. Their ancestors likely lived in the desert areas for a few thousand years at least, however prior to this they likely would have inhabited more boreal climates being close to mountain ranges and ultimately hailing from somewhere in south Siberia.

A good amount of these mummies were described as having red and blond hair, which you can also see in the mummies above. Although knowing that hair can change colour over time due to external influences, this is very unlikely to have happened in the Tarim Basin however, as the most common change in colour comes from water damage, and the Tarim Basin is one of the driest places on earth.

What we can tell from the genomic ancestry of these samples is that one of the Gumugou samples (GMGM1) had a call for the A allele of rs11547464 on the M1cr gene. This is one of the mutations associated with red hair. Another sample from Xiaohe (L5209) was positive for the C allele of rs12821256 on the KITLG gene, associated with blondism. The oldest sample with this snp is Afontova Gora 3, a sample of a palaeolithic female Ancient North Eurasian. Although we cannot know for certain if these individuals actually had blond or red hair, the presence of these two snps give a genetic basis for the appearance of red and blonde hair amongst the remains of the bronze age tarim populations.

Taking all these anthropological and genetic data points in mind, AncestralWhispers made several reconstructions based on the skulls of the Tarim natives. The first one was based on skull 9 from burial M29 of Gumugou:

Another reconstruction was based on the Xiaohe male from burial M24:

Tianshanbeilu cemetery

Beyond the Taklamakan desert and their inhabitants, Xinjiang during the bronze age also housed other populations. In Hami, the eastern part of Xinjiang we have a rather large cemetery known as the Tian Shan North road cemetery, or Tianshanbeilu. The Tianshanbeilu cemetery had several phases, going from 2100 BC until 1000 BC [8], more or less covering the entire bronze age.

The culture and population at Tianshanbeilu was primarily of eastern origin, as the site reveals many parallels to the late stone age/bronze age populations of Gansu and Qinghai. It seems that these populations had migrated westwards and established themselves in Eastern Xinjiang. At Tianshanbeilu we also see trade contacts with more western populations, in particular the Chemurchek culture of Dzungaria were noted to have significant contacts with the people of Tianshanbeilu.

An article has provided some anthropological materials of the remains at Tianshanbeilu and presented some of their craniums which you can see below:

Male skulls:

Female skulls:

On the AncestralWhispers website a reconstruction of one of the males of Tianshanbeilu had already been featured:

The east asian side of Tianshanbeilu seems to fall in the north chinese anthropological formation, in accordance with the yellow river neolithic origin of the peoples in East Xinjiang. It is clear that West Eurasian peoples were present at Tianshanbeilu, but which kind? The Xiaohe-Gumugou types, Afanasievo-Chemurchek populations or Andronovo populations? These do not have to be mutually exclusive, but archaeology of the Tianshanbeilu, Qijia and Siba cultures indicate significant contact with the Afanasievo-derived Chemurchek peoples.

Ancient DNA from these sites also indicate Mtdna U4, U5 and W [9], which differ from the Xiaohe culture MtDNA lineages being almost exclusively C4, with one sample having mtdna R1b1. This means it is unlikely that the western populations at Tianshanbeilu were Tarim Basin related. Chemurchek or Andronovo-related on the other hand is very much possible, and given the archaeology the former is the more likely candidate of the two. Therefore this sampleset carries quite some significance, as the anthropology of the Chemurchek populations has not been strongly investigated.

The Chemurchek samples varied a bit genetically, but they all were a mixture of Afanasievo, South Siberian and Central Asian populations, with some samples having BMAC-related ancestry. This is quite interesting because Tocharian is generally held to share the BMAC-related substrate that Indo-Iranian languages have, with genetic signals such as these providing a window for independent acquisition of said substrate rather than through an Indo-Iranian mediary.

Andronovo culture

The Bronze age of Xinjiang also saw the appearance of Andronovo populations. Not so much deep in the Taklamakan desert, but the mountainous Pamir, Tianshan, and Altai regions all housed Andronovo populations. These predominantly seemed to have been of Fedorovo extraction, although the Andronovo-derived Karasuk peoples were of Alakul extraction.

At Xiabandi we have physical remains of Andronovo peoples from the Pamir regions. The Authors suggested that due to the lack of evidence for earlier populations, the Andronovo people might be the first to have inhabited the region [10]. From an anthropological perspective the closest match for these samples were Srubnaya and Catacomb culture samples. There seemed to have been two dietary strategies at Xiabandi, one more meat based and another more produce based. There were no burial distinctions between the two dietary strategies, and they are contemporary interestingly.

The same article also provided a chart of measured data between various bronze age populations which comes in quite handy as well.

I used google translate and some names came out a bit odd. Here are they in terms a bit more understandable:

Shimosakachi bronze group = Xiabandi cemetery

Cave tomb group = Catacomb culture

Ancient shaft tomb culture = Yamnaya culture

Wooden coffin tomb group = Srubnaya culture

The Andronovo population is fairly well researched in physical anthropology, a legacy of most of the Andronovo sites being in former Soviet countries where physical anthropology was a significant field in the study of these ancient populations. I don’t think an elaborate investigation in the anthropology of the Andronovo population is warranted for this discussion so I will be moving on to the iron age.

Iron Age

Different countries have different systems for defining the iron age. Colloquially speaking I tend to refer to periods between the 10th century BC and 1st century BC as the iron age, even if in the respective regions this would be considered the bronze age. I am not alone in doing this, it is very common in Chinese literature to refer to areas which would be considered iron age by western standards as bronze age, because the main Chinese regions were still in the bronze age.

The iron age is an interesting period in Xinjiang because it is formative for the two main attested languages in Xinjiang, the Khotanese-Tumshuqese languages, an Eastern Iranian subgroup you might know of as Khotanese Saka, and the Kuchean-Agnean languages, which you might know as Tocharian. Unfortunately Khotanese Saka and Tocharian are two misnomers whose catchy names stuck around.

The archaeology of the iron age Xinjiang is one I find very interesting. We also see the development of rather unique material cultures such as the Yanbulake culture, the Subeixi culture or the cemeteries of Zaghunluq and Gavaerk within the Tarim Basin. While all of these had significant material influence from populations outside of Xinjiang, they all developed material cultures quite distinct with traditions you can only find in this part of the world.

From an anthropological perspective this is an interesting period too because this is when we see the prolific spread of a major anthropological type in Xinjiang, the East-mediterranean populations. Appearances of the third major type, the Pamir-Ferghana type also occur, but only in areas part of or adjacent to the Eurasian steppes.

Liushui

Liushui is one of those sites that just prove how Xinjiang is one of most bizarre regions in the world when it comes to prehistoric populations, as if those Siberian relict mummies with red and blonde hair weren't strange enough. Liushui is another site with a rather unique population present.

Situated in the Yutian county of the Hotan region, Liushui is an early iron age site of a pastoral population. If you read up on the archaeology of the site, the first impression is that you are looking at Scytho-Siberian peoples derived from Karasuk culture migrants to the southwestern rim of the Tarim Basin. This was my initial impression too, until we got ancient DNA from this site last year. If you had read my previous blog entries on ancient Xinjiang you might have seen me extensively cover it. The reason why Liushui is fascinating is because of the autosomal profile carried by the populations there.

I had already covered the genetics of the people at Liushui in two of my previous blog entries (here and here) so I do not feel the need to include the models here again. One sample, C1246 was mostly Central Asian, with a mixture of Andronovo, Bactria-Margiana archaeological complex and native Tian Shan populations (Aigyrzhal_BA) with some South Siberian/Northwestern Mongolian ancestry too, likely coming from peoples similar to those of Deer Stone Khirigsuur complex (Khovsgol_BA). This sample wouldn’t stand out too much in most areas of Central Asia but he was labelled an outlier due to his steppe ancestry. C1235 on the other hand was a sample purely a mix of Siberian/Northwestern Mongolian and Central Asian ancestries without any Andronovo input at all. No such samples had been uncovered so far yet, and finding one in the iron age is quite bizarre to say the least. Furthermore, it was this sample that was the “regular” one, as the other Liushui samples all had labels indicating similar genetic profiles.

The Liushui samples show a separate migration of Khovsgol_BA related peoples separate from the main Scytho-Siberian expansions towards the southwestern Tarim Basin. It also suggests that Aigyrzhal_BA type populations probably persisted until the later bronze age or perhaps even the iron age. We also have genetic samples from the Jirzankal site further east, and these all had fairly low steppe ancestry but significant amounts of Aigyrzhal_BA and Khovsgol_BA ancestry with Khovsgol_BA related patrilineal lineages, which to me suggests their profile arose due to a mixture of Central Asian Iranians and the people of Liushui.

An article studied the skulls present at Liushui and found that they were a mixed population, with a slight predominance of east asian features [11]. Unfortunately the size of the images wasn’t great, and therefore the quality isn’t all too good. The authors divided the articles up in three groups: Eastern features, western features, and mixed features.

In my opinion these largely seem to belong to the same population, as you would naturally expect some variation between a recently mixed west/eastern population. It might be that some of the western feature skulls were Andronovo derived like that Liushui2 sample.

One side of the Liushui anthropological expression should be ascribed to a population similar to the previously mentioned people of Aigyrzhal from Kyrgyzstan. These were pastoralists of a mixed genetic origin, one half of their ancestry being ANE-rich and similar to that of the Steppe Maykop and Kumsay peoples, the other half being similar to the eneolithic and bronze age Southern Central Asian populations.

You might have seen AncestralWhispers make a reconstruction of them before:

The other significant element should be seeked in the bronze age populations of the Altai-Sayan region, particularly with the population of the Deer Stone Khirigsuur complex. These were pastoral horsemen, with their petroglyphs indicating the usage of charioteering. They may have ridden horses as well. These people had significant contacts of the Andronovo-derived Karasuk culture, ancestral to the iron age Scythians, and there were bidirectional cultural influences between the two.

Deer stone stelae from the Hovsgol Aimag, Northern Mongolia

The Deer Stone peoples were mixed between a population with substantial Ancient North Eurasian ancestry, likely the populations from the neolithic Altai, as well as the East Asian people of neolithic Mongolia. Some samples show signs of genetically mixing with Andronovo populations but the vast majority of the samples did not have such ancestry.

Unfortunately I do not have any cranial information to provide you when it comes to this population. The next best thing would be genetically similar or closely related populations. I think this bust of a bronze age Glazkovo male from the cis-Baikal region could perhaps be of relevance as these populations had similar ANE/East Asian ratios and have a connection in their uniparentals coming from similar ANE-rich populations:

The issue here is that while they might have similar ratios of ANE ancestry, their east eurasian ancestry comes from slightly different sources: Baikal neolithic and North Mongolian neolithic populations. While these might be genetically similar, I do not know if they would have been craniometrically similar. That said if you look at this bust, it matches some of the features seen at Liushui such as a dolichocephalic skull and a fairly high face.

Perhaps another case which could be of help is this reconstruction of a “Chemurchek” male from Ulgii. I put Chemurchek in quotations because while the burial rites were similar and obviously Chemurchek-influenced, the people biologically seemed different from the main Chemurchek populations in Dzungaria.

We have ancient DNA from Ulgii remains which confirm said biological distinction, the samples were quite similar to those from late bronze age Khovsgol. The issue is that this is a single skull which cannot be connected to the Ulgii DNA samples. It could very well be that this individual had more ANE ancestry, or did have genuine Steppe_EBA ancestry which the genome sample lacked, or perhaps this sample had less western ancestry. Hard to say really. This is how the sample was described however [12]:

Its anthropological type shows a significant Mongoloid component. Intergroup comparison revealed its significant morphological differences from markedly Caucasoid groups, including the Afanasievo culture of South Siberia and Central Asia. This excludes the morphogenetic continuity of the Chemurchek phenomenon from the antecedent Afanasievo population. The individual from Hulagash bears the greatest anthropological similarity to the Neolithic-Eneolithic and Early Bronze Age populations of the Circumbaikal region (Serovo and Glazkovo cultures) and the Barnaul-Biysk Ob area (Itkul and Firsovo XI burial grounds dating back to the pre-Bronze Age; Early Bronze Age burial grounds of the Elunino culture). This is obviously a manifestation of a shared anthropological substrate, since the anthropological component of the Baikal type (which the population of the Elunino culture included) was recorded in the Neolithic-Eneolithic materials from the northern foothills of the Altai Mountains. Remarkable morphological similarities between the individual from Hulagash and the bearers of the Elunino archaeological culture reinforce the assumption that there is a cultural affinity between the Chemurchek and Elunino populations of the Early Bronze Age.

Something along the lines of the Glazkovo male and the Ulchii male should be a reflection of the phenotypic profile of the Siberian side Liushui. If you ask me, sticking those two craniofacial profiles together should get you something similar looking to the Liushui population.

Based on the genomic ancestry of the Liushui peoples and their anthropological features, AncestralWhispers made a reconstruction of the one the Liushui peoples, modeled on skull M5:

East Pamir

Another population worth looking at for the study of ancient populations are the inhabitants of the East Pamir region, often dubbed “Pamir Saka”. These people are considered a benchmark of the Indo-Afghan race and therefore are quite often mentioned in the literature for comparative purposes.

I have very strong disagreements about these people being labelled “Saka”. They were not nomads of the steppe tradition, the sites in China belonging to this group (being more thoroughly and recently excavated than the ones in Tajikistan) indicate a degree of sedentarism and agricultural production deviating significantly from the nomadic Saka, as do their burial rites. From an archaeological perspective at most you can call their material culture Scytho-Siberian influenced We are clearly dealing with a southern central asian population, fairly similar to modern Pamiris in all likelihood. It goes without saying that the anthropological type of Scytho-Siberians were not of this extraction.

If these were Saka, then their economies, physical features and burial rites deviate significantly from the regular Saka. A final nail in the coffin would be historical records, as there is no historical precedent for Sakas being in this region to begin with and we have a fairly decent record of where scytho-siberian nomads were present.

We have a good amount of anthropological materials of these peoples as their presence crosses the borders of China and the former Soviet Union via Tajikistan. Here are three Pamir Saka males from Tajikistan, from Tamdy, Baha-Bashi and Ak-Beit sites respectively:

AncestralWhispers had already made a reconstruction of one of these males, which you can see here:

One of Han’s articles featured male Pamir skulls from western Xinjiang, and as you can see they belong to the same anthropological type as the earlier presented Pamir skulls:

Wubao - Yanbulake culture

The Yanbulake culture is one of those iron age material cultures of Xinjiang which cannot be easily ascribed to a singular origin. Just like the earlier Tianshanbeilu site, this culture was at the crossroads of “east” and “west”. A significant component of this culture can be ascribed to the Qijia and Siba cultures of Qinghai and Gansu. An influence of the Chemurchek culture had also been noticed in the bronze age period before the Yanbulake culture, and the Yanbulake culture could best be seen as a syncretic culture between Chemurchek and the populations of the Upper Yellow river, a process already beginning hundreds of years prior Yanbulak as shown at Tianshanbeilu [12].

The Yanbulak cemetery, Liushuquan, Hami

This cemetery is situated on an earthen hill called Yanbulak nearby Liushuquan, Hami region. The rectangular graves were lined with adobe bricks made of sand and earth from the Gobi. Their age is about 3 100-2500 years B.P. Most of the graves have been disturbed and bone preservation is poor. About 76 graves have been excavated but only 29 complete skulls were obtained. Twenty-one of them are of clear East Mongoloid character, eight can be classified as belonging to the Western race. The general morphological character of the skulls classified as Mongoloid are elongated with fairly wide orbits and close to that of the East Tibetan populations. The skulls with Western racial character are close to that of the Gumugou cemetery of the lower reaches of the Kongque River in their morphology (Han Kangxin, 1990). In a word, elements of Eastern and Western races co-existed in the ancient populations of the Hami region, but the former are dominant. According to the unearthed painted pottery, the ancient culture of the area bears a close relationship with that of the Bronze Age of eastern areas such as Gansu and Qinghai (Kokonor) (Han Kangxin, 1990).

Aside from this image from two skulls from Yanbulake, I don’t have any direct anthropological materials from the Yanbulake cemetery itself. I do have some from Wubao however, another cemetery of the Yanbulake culture.

At Wubao the physical remains were divided into two categories: the C-group and the M-group [13]. You can guess what those letters indicate. A significant number of the remains were described as being of East Eurasian origin (M-group). This should clearly be related to the Tianshanbeilu, Qijia and Siba culture peoples in the Eastern parts of Xinjiang.

Just like at Tianshanbeilu, at Wubao the same scenario of both western and eastern populations being buried in the same cemetery occurred. The degree of westerners at Wubao was a bit higher than at Yanbulake, which is a trend that increased over time. In the article three male skulls were provided, one of them belonging to the M-group:

The anthropological type of the C-group people at Yanbulake had been described as being of the Proto-Europoid type. Given that we know ANE-rich and Afanasievo populations were both described as “Proto-Europoids'' in Chinese anthropological works, this could perhaps be an indication that the C-Group Yanbulake populations were of such extractions.

Things may not be that simple though. From experience I know that Eastern Scythians such as Pazyryk had been described as physically resembling Afanasievo quite a bit, while genetically they were a combination of Andronovo and South Siberian populations. As we know Andronovo were physically similar but Afanasievo and Yamnaya populations tended to be a bit more robust, Andronovo populations also had a significant amount of Anatolian neolithic farmer ancestry, and over time also acquired some Bactria-Margiana related ancestry which deviated their phenotype from the earlier steppe inhabitants.

So in a sense similar to the Xiaohe culture people, I don’t think we should instantly assume that Proto-Europoid features indicate a close genetic similarity to Afanasievo or Andronovo populations. It could very well be that the Proto-Europoid examples had southern central asian and east asian ancestries which together with western steppe and ANE-related ancestries just coalesced in a form similar to Proto-Europoids. If you pay close attention to the C-group examples, some features point towards east asian ancestry being present in this population.

On the other hand, connections to Chemurchek were noted for the Yanbulake population as well as significant archaeological relationships with material cultures to their west such as the Subexei culture, although such relationships do not have to be intrinsically genetic.

AncestralWhispers made a reconstruction of one of the two caucasoid males from Yanbulake:

Kizil

The Kizil cemetery lies near the Kiziltur or Kezi’er village in Baicheng county, Aksu prefecture of Xinjiang and dates to 700-500 BC. Aside from the presence of glass beads I cannot find much about the site. Kizil sits about 13 kilometers to the west of Kuqa, which used to be a Tocharian city-state, making it likely that this iron age population at Kizil also were Tocharian. This would be about as west as Tocharian was present on the northern rim.

A study of 23 craniums from this cemetery showcased that the populations at Kizil were caucasoid populations, approximating to the Indo-Afghan type. However they were described as not being exactly East-mediterranean/Indo-Afghan, deviating towards more northern and northeastern populations of the Proto-Europoid types due to lower skulls, lower orbitals and also having broader noses when compared to more classical mediterranean populations such as those of the Pamir region [14].

One of the skulls of Kizil was presented in the article, you can see it here:

Looking at this map of iron age pottery traditions of Xinjiang we can see that in the north there is a division between gray (unpainted) pottery and painted ceramics to the east, with the area in between Aksu and Kucha being the border in the north [15].

The population which expanded into the Tarim Basin from the west is part of the Chust-Aketala culture which primarily had painted ceramics but the sites on the route towards the Tarim Basin mostly utilised grey ceramics. To a degree the distribution of grey ceramics could be associated with the spread of these agricultural “mediterranean” populations as well as the Khotanese-Tumshuqese language. However you can see that immediately east of Aksu we already see a P and around Kucha to Turfan it is just painted ceramics.

Kiziltur sitting in the painted ceramic zone but having a geographic proximity to the grey ceramic zone to the west could be a good explanation behind the anthropological findings, a Proto-Europoid shifted variant of the Xinjiang Indo-Afghan populations.

The same article also gives a description of the skulls of the Alagou cemetery and the Subeixi culture of the Central-Eastern Tian Shan. These were described as Europoid peoples of partial Mediterranean origin with no further elaboration on the other components these populations would have had. Considering that the deviation from mediterranean in the Kizil population was towards Proto-Europoid, it might be that the Subeixi and Alalgou populations were further shifted towards Proto-Europoid.

Alagou

The Alagou cemetery is an iron age cemetery on the southern portion of the Turpan depression in Xinjiang. Spanning across the iron age and being split into two phases, the Alagou cemetery is the type site for the iron age Alagou culture. The Alagou cemetery and Subeixi cemetery share a lot of traditions and should be considered as one cultural zone. Both Subeixi and Alagou have very strong parallels to the burial traditions of the Jushi peoples, one of the Tocharian peoples of antiquity. Therefore it is quite likely that the iron age population of Alagou were Tocharian speakers as well.

THe anthropological materials from Alagou date to about 600-100 BC. The remains of this cemetery has been described as being one of the most “diverse” in ancient Xinjiang as it had representation from the four main “races”of ancient Xinjiang: Proto-Europoid, Mediterranean, Pamir-Ferghana and Mongoloid. In addition, other skulls showcase mixing of traits from these various types [16]. Going by the map of Kangxin Han, amongst the 58 skulls studied Proto-Europoid was the most prevalent, followed by Pamir-Ferghana, Indo-Afghan and Mongoloid in that order.

I have an image of three skulls from Alagou, representing the three “caucasoid” types found at Alagou. Unfortunately I don’t have more information to offer:

If you were to ask me, the left skull looks a bit similar to the ones at Yanbulake. The one on the right is obviously one of the Pamir-Ferghana skulls, and the middle one of the Indo-Afghan skulls. Indo-Afghan in this case is probably similar to the scenario at Kizil, where it is clear you are only dealing with partial Indo-Afghans. The Pamir-Ferghana samples are more interesting to me, because the geographic location of Alagou does allow for significant contact with Scytho-Siberian peoples. It might be that it is just phenotypic variation but I think Scytho-Siberian ancestry in some of these samples might not be out of order, the cultures in this area certainly had quite some Scytho-Siberian material influence in terms of archaeology after all.

Gavaerk is an iron age cemetery on the Kunlun mountain range in Qiemo, Xinjiang, dating to about 400-100 BC. The cemetery was used for several centuries and may have belonged to a particular family or tribe. The people at Gavaerk likely were pastoralists, which frequently rode horses going by their post-cranial physical remains [17].

The cemetery of Gavaerk was contemporary to that of Zaghunluq, and also quite close to it geographically. The burial descriptions of the earlier phase at Gavaerk are quite similar to the Zaghunluq cemetery burials which might suggest a cultural and genetic connection between the two. The Zaghunluq cemetery is the grave where the famous Cherchen man was discovered.

Three skulls from the Gavaerk cemetery were presented in the article, one female and two male (in that order):

M3G - female

M3B - Male

M20 - Male

This skull showed clear artificial cranial deformation, a practice which became prevalent during the later parts of the iron age in areas of Central Asia. Sarmatians, Kushans and the later European Huns were peoples which all practised artificial cranial deformation. This practice also became prevalent in Xinjiang, as can also be seen in these skulls from Chahuwu cemetery III dating in between 100-200 AD.

Unlike the later European and Central/South Asian Hunnic groups amongst the various peoples of the Xiongnu empire this custom was not practised, aside from the peoples in Xinjiang under Xiongnu hegemony. How this tradition became prominent amongst European and Central Asian Hunnic groups is still unresolved, but perhaps populations in Xinjiang played a significant role in the spread of this tradition.

To get back to the Gavaerk peoples, when compared to other populations the most similar ones were the Yanbulake C group (the west eurasian one), Chawuhu cemetery 4 and Duogang cemetery. In this article they were all described as primarily “primitive European”, with some features being indicative of more “modern human” traits such as a heightened face and narrow nose. Just like in other articles Primitive European seems synonymous to Proto-Europoid, thus the Qiemo peoples should also belong to this cluster. The deviations in facial height and nasal width compared to standard Proto-Europoids may be related to mediterranean admixture in the population.

The Gavaerk people were featured in the article Prehistorical East-West admixture of maternal lineages in a 2,500-year-old population in Xinjiang.This article gave insight into mtdna but not much beyond that. If the genetics of the people at Zaghunluq are anything to go by, the people of Gavaerk likely had a complicated genetic mixture. The Zaghunluq really were a mishmash of everything, ANE-rich populations, steppe populations, southern Central Asian and East Eurasian populations.

This genetic composition combined with Proto-Europoid classifications could be related to the inference I made earlier about Yanbulake, that Proto-Europoid features can still manifest in a population with considerable mediterranean and east asian ancestries. In this case we are probably dealing with a population of Indo-Iranian extraction rather than Afanasievo derived given that these are people of the same tradition as the people of the Zaghunluq cemetery.

Stature

The same article also did post-cranial analyses, one of them being a measurement of stature. Stature estimation is a complicated topic as the primary method of estimating stature is by taking measurements of particular bones and comparing them to sizes of populations of which the stature is known. The complex part lies in the fact that ratios of bone lengths not only differ across populations, they vary across time periods too.